Click on the image to zoom

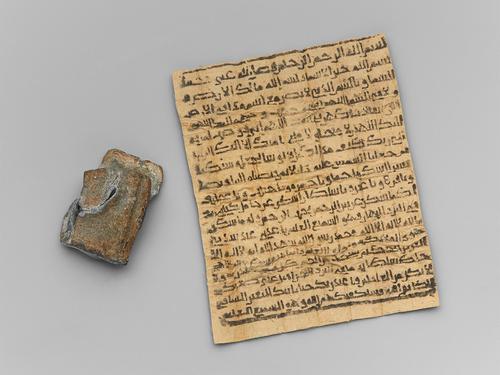

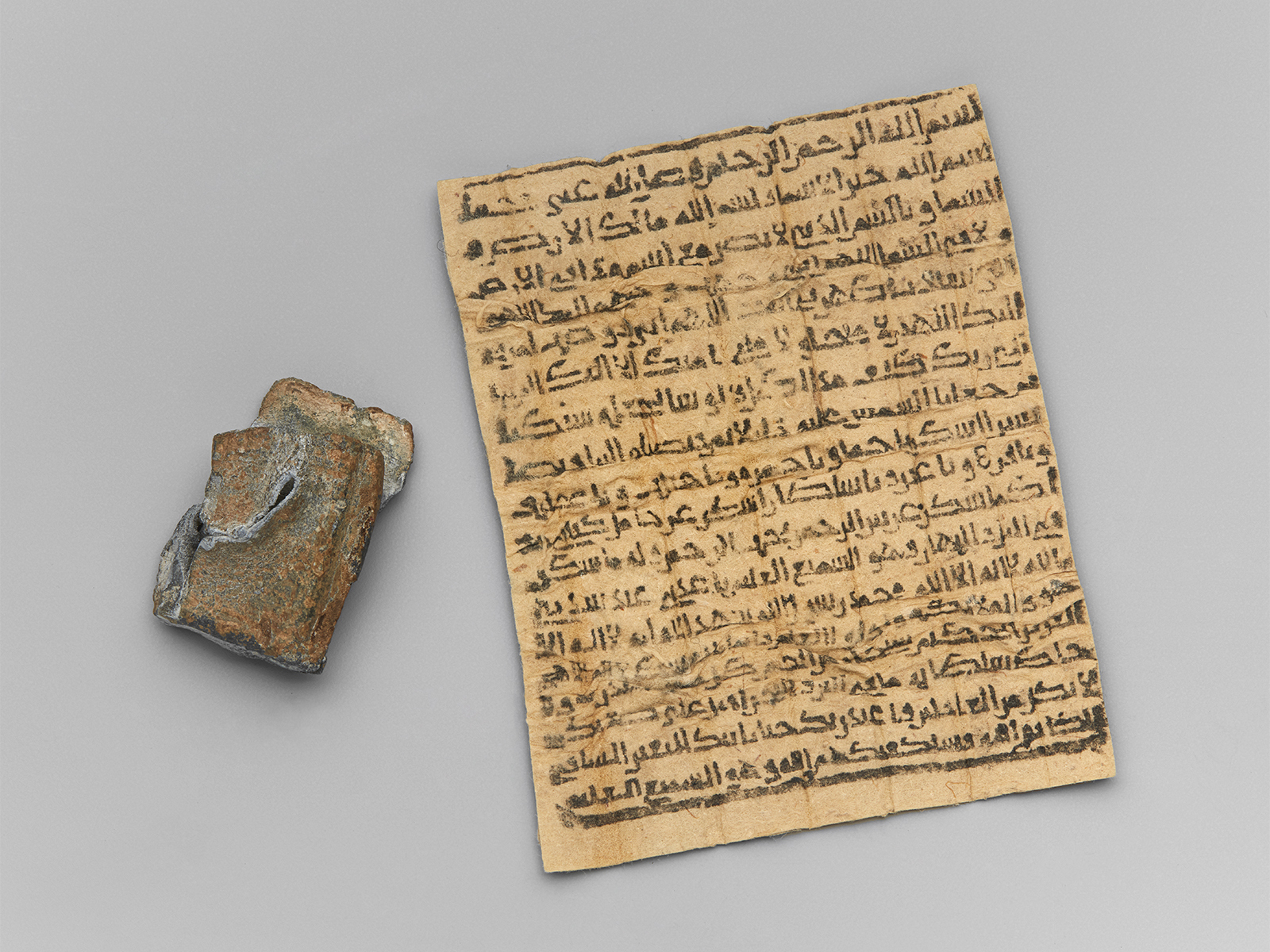

Printed amulet with box

- Accession Number:AKM508

- Place:Egypt

- Dimensions:Amulet 7.2 x 5.5 cm; Case 2.7 x 1.3 cm

- Date:11th century

- Materials and Technique:Paper, lead

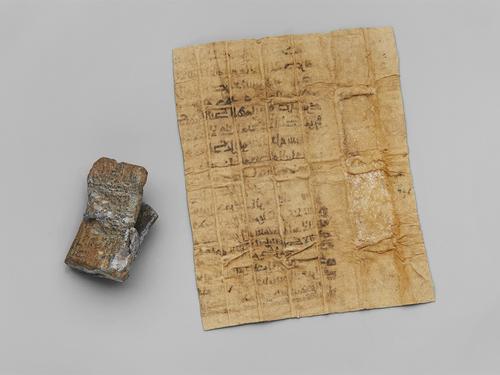

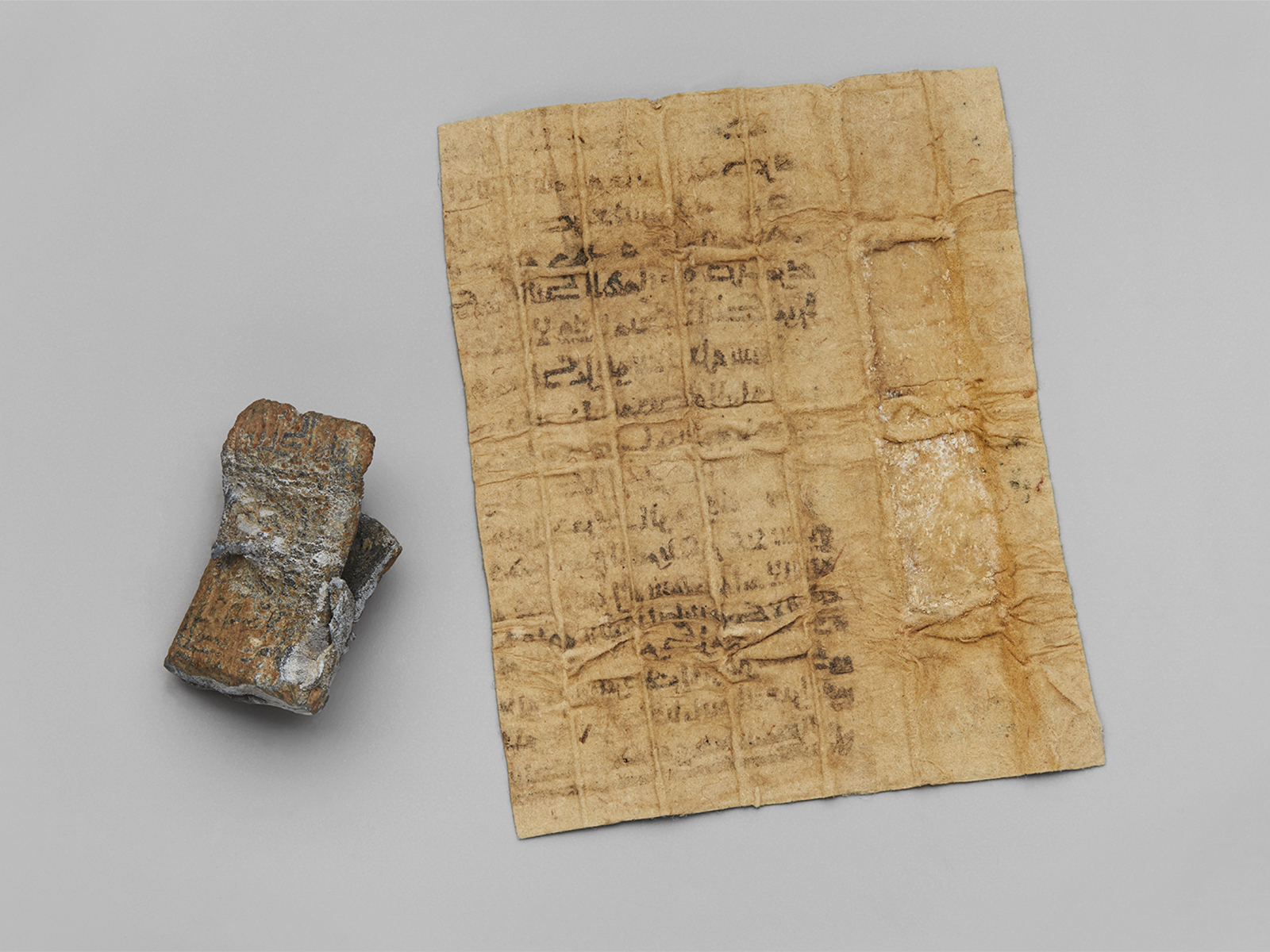

Intended to bring good fortune to its owner, this miniature paper amulet has been folded many times to reduce its size, making it easy to wear and transport within its lead case. It belongs to a body of talismanic objects made in the medieval Mediterranean that do not merely include handwritten texts and symbols, but rather incorporates Qur’anic verses, prayers, and designs. Both script and symbol were likely executed with a block print or die (tarsh). Its lead case likely had lugs (now lost) which enabled the amulet to be sewn to the owner’s shirt or suspended from the body.

Further Reading

This tiny “carry-on” amulet most likely remained sealed shut, its scripted contents invisible to an owner who perhaps was neither literate nor wealthy enough to purchase a larger and more expensive handwritten amulet. Even though it may not have been read, its texts nevertheless include Qur’anic verses—among them, on lines 13–15, Qur’an 3:18 (Al ‘Imran), which is considered particularly apotropaic or powerful at warding off evil influences. It also contains invocations to God as an intercessor (shafi‘), and its last line addresses the owner with a verse from the Qur’an that proclaims: “So God will safeguard you from them. He is All-Hearing and All-Knowing” (Qur’an 1:137: fa-sayakfikahumu Allahu wa huwa al-sami‘ al-‘alim). These lines make it clear that both God and the Qur’an act as the supreme sources of knowledge, protection, and intercession.

The lead case is inscribed with surat al-Ikhlas (Qur’an 112:1–4). This short Qur’anic chapter instructs the worshipper to proclaim God’s eternal singularity and it is believed to be especially protective. As with the amulet text, here thrives a tension between imagining God as the ultimate Protector and the amulet as a material item that objectifies this otherwise amorphous divine energy. This tension likewise extends to amulets written in ink that also appear to have been burrowed within sealed cases (see AKM536). In this way, such amulets become acceptable forms of magic that do not contravene any religious doctrine or law.

Moreover, this diminutive amulet’s texts are written in minute Kufic script whose angularity and lack of vowels and diacritics make it particularly suitable to the block printing process. Other amulets in international collections make use of a similar process of mechanical reproduction and micro-Kufic script. Generally attributed to the Fatimid period (909–1171), related amulets either comprise a single sheet of paper or else are made in a scroll format. One scroll now held in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, [object 1978.546.32], whose texts bear similarities to the Aga Khan Museum’s amulet, also includes at its top the seal of Solomon, one of the most common amuletic designs.

The twin goals of portability and preservation prompted amulet-makers to explore a range of creative strategies, chief among them size reduction and encasing. Many amulets and talismans therefore make effective use of miniaturization, enabling owners to wear them close to the body and to carry them with ease.

— Christiane Gruber

References

Bulliet, Richard. “Medieval Arabic Tarsh: A Forgotten Chapter in the History of Printing,” Journal of the American Oriental Society 107.3 (1987): 427–438. DOI: 10.2307/603463

Dawkins, J.M. “The Seal of Solomon,” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society (October 1944): 145–150. DOI: 10.1017/S0035869X00099019

D’Ottone, Arianna. “A Far Eastern Type of Print Technique for Islamic Amulets from the Mediterranean: An Unpublished Example,” Scripta: An International Journal of Codicology and Paleography 6 (2013): 67–74.

Gruber, Christiane. “From Prayer to Protection: Amulets and Talismans in the Islamic World,” Power and Protection: Islamic Art and the Supernatural, ed. Francesca Leoni, 33-52, esp. 42–43 and fig. 23. Oxford: Ashmolean Museum, 2016. ISBN: 9781910807095

Leoni, Francesca. “Sacred Words, Sacred Power: Qur’anic and Pious Phrases as Sources of Healing and Protection,” Power and Protection: Islamic Art and the Supernatural, ed. idem, 53–65. Oxford: Ashmolean Museum, 2016. ISBN: 9781910807095

Regourd, Anne. “Amulette et sa boîte,” Chefs d’oeuvre islamiques de l’Aga Khan Museum, ed. Sophie Makariou, 130–131, cat. no. 45. Milan and Paris: Musée du Louvre, 2007. ISBN: 978-88-7439-442-5

Al-Saleh, Yasmine. “Amulets and Talismans from the Islamic World” Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2010.

Schaefer, Karl. Enigmatic Charms: Medieval Arabic Block Printed Amulets in American and European Libraries and Museums. Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2006. ISBN: 9789004147898

----------. “Eleven Medieval Arabic Block Prints in the Cambridge University Library,” Arabica 48/2 (2001): 210–239. DOI: 10.1163/15700580132322446

Treasures of the Aga Khan Museum: Arts of the Book & Calligraphy, 40–41, cat. no. 14. Geneva and Istanbul: Musée du Louvre, 2010. ISBN: 9786054348084

Note: This online resource is reviewed and updated on an ongoing basis. We are committed to improving this information and will revise and update knowledge about this object as it becomes available.