Click on the image to zoom

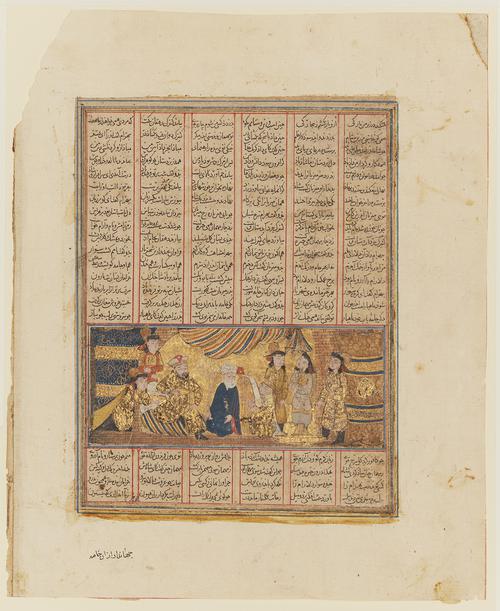

Bahram Entertained By Arezu, Daughter Of Mahyar The Jeweller

Folio from a dispersed copy of Firdausi’s Shahnameh (Book of Kings)

- Accession Number:AKM16

- Place:Western Iran

- Dimensions:24 x 19.2 cm

- Date:late 13th or early 14th century

- Materials and Technique:ink, colours, gold, and silver on paper

This folio from the dispersed copy of the “Second Small” Shahnameh (Book of Kings) illustrates an episode concerning the historical Sasanian king, Bahram (or Vaharam) V (r. 420–38). It shows the visit paid by Bahram Gur to the home of one of his subjects.

Bahram Gur,“that great hunter,” had performed another of many feats with his great bow, this time killing a pair of savage lions who would have preyed on the great flock of Mahyar’s sheep; and the head shepherd, not recognizing Bahram, addresses him, wishing to thank the brave archer and also praising the justice of the Shah’s rule. Bahram—still incognito—decides to visit the jeweller’s house where, says the shepherd, he will hear toasts and the sound of a harp. Indeed, Mahyar has “just one daughter, who plays the harp” and she does so, seated before both her white-bearded father and the Shah.

Further Reading

Here, Bahram is gold-robed but wears a simple cap. His attendants are also garbed in rich robes, either of golden fabric or with golden (Chinese) mandarin-squares on the breast, and all wear black Mongol caps trimmed with huge puffs of owl-feathers [1]. Mahyar’s sober dark-blue robe has red-lined sleeves; and he wears a high white turban. Arezu is the only woman in the painting; the jeweller’s daughter has large golden discs at her ear, and the white veil falling behind her is held in place at her brow by a wide golden fillet.

The evening’s entertainment finishes just as Bahram’s chief minister had predicted: “Now the king is going . . . to ask her father for that young woman’s hand.” The king’s actual identity remains unrevealed until the next morning, when the shah’s groom has hung Bahram’s jewelled golden whip on Mahyar’s door.

The painting is again designed as a horizontal strip extending across the written surface of the page but, in contrast to the first two paintings from this manuscript (AKM85, AKM18), this picture is an elaborately furnished interior scene. A billowing striped curtain drapes the large arched golden opening in the middle of the picture, and equally lavish curtains hang at either side. Such textile richness accords with the subject of the story: one of the protagonists is the old jeweller, Mahyar, who is rich, with “donkey loads of fine jewels as well as gold and silver.”

Introduction to the “Second Small” Shahnameh

The “Second Small” Shahnameh, also now dispersed, is another of the earliest surviving illustrated copies of the Persian national epic composed by Abu’l-Qasim Mansur Firdausi (d. 1020). Firdausi composed it around the turn of the 11th century, conveying in more than 50,000 rhyming couplets the lives and adventures of 50 Iranian kings before the arrival of Islam.

The “Second Small” Shahnameh contains almost identical material to the “First Small” Shahnameh [2], though its contents are far more widely scattered. Both manuscripts were likely made at the same time and place: somewhere in western Iran towards the end of the 13th century, or very early in the 14th.[3] There are subtle technical differences between these copies. The “Second Small” Shahnameh has a somewhat different, and also larger program of illustration. Moreover, in their dispersal, each copy was treated differently: folios of the “Second Small” Shahnameh were almost never pasted onto a larger mount, as are so many from the “First Small” Shahnameh (including AKM19). This treatment has two primary implications. First, the text on the reverse of the folio can also be read; second, any illustration taken from it can be identified within the larger poem, ideally by reading the text in one of several Persian editions of Firdausi’s masterpiece.[4]

Four folios from the “Second Small” Shahnameh in the Aga Khan Museum amplify the themes and the range of early Shahnameh illustration: two focus on its heroic figures (AKM18, AKM85), while the other two illustrate episodes from the historical section, dealing with events in the lives of the Sasanian kings Shapur II (r. 304-379) (AKM17), and Bahram V (r. 420-438) (AKM16).

— Eleanor Sims

Notes

[1] The owl feathers in caps offer corroboration for a date. After the Mongol conquest, Ilkhanid male headgear distinguished rank and position by the feathers of different birds.

[2] The term coined by Ernst J. Grube in Muslim Miniature Paintings from the XIII to XIX Century from Collections in the United States and Canada (catalogue of an exhibition at the Cini Foundation, Venice, and Asia House, New York City), (Venice: N. Pozza, 1962), 22–8.

[3] Instead of “around 1300 in Baghdad,” a now-untenable attribution largely accepted since Simpson’s publication of 1979, 273–80. This was based upon information in the colophon of a Persian copy of Sa‘d al-Din al-Varavini’s Marzban-namah (in the Library of the Archaeological Museum in Istanbul, MS 216); the manuscript was completed in Baghdad on 10 Ramadan 698/19 May 1299 but has just three small illustrations; see also Notes 4-5 for “First Small” Shahnameh.

[4] Critical editions of the Persian text: Firdausi Shakh-Name: Kriticheskii Tekst, ed. Y. E. E. Bertels, 9 vols. (Moscow, 1960–71); Abu’l-Qasim Firdausi Shahnamah, ed. S.M. Dabir Siyaghi, 5 vols. (Tehran, 1370 sh/1971); and Abu’l-Qasim Ferdawsi, The Shahnameh, ed. Djalal Khaleghi-Motlagh, 8 vols. (New York, 1988–2009).

Note: This online resource is reviewed and updated on an ongoing basis. We are committed to improving this information and will revise and update knowledge about this object as it becomes available.