Click on the image to zoom

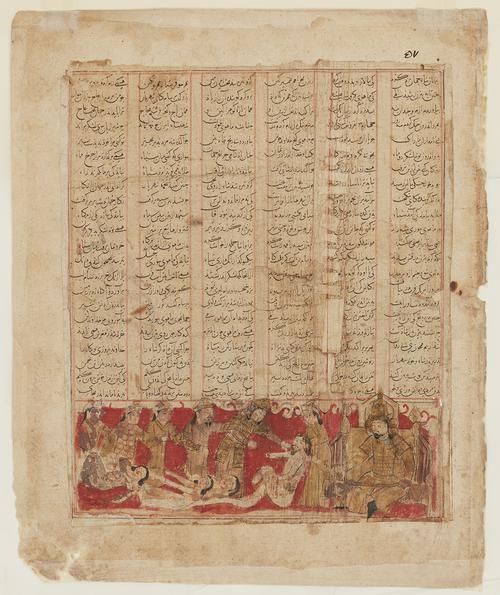

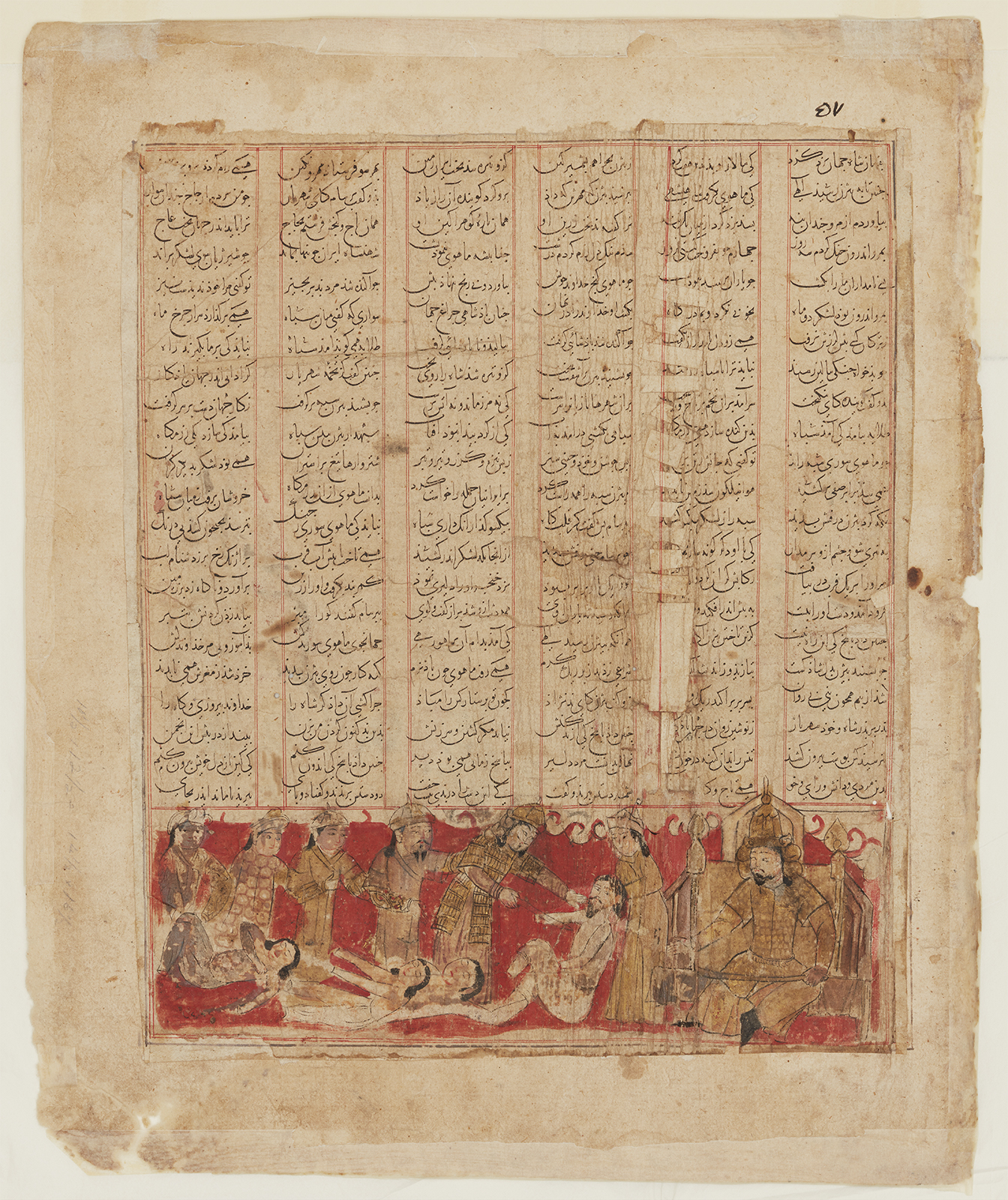

Bizhan kills Mahuy and his sons to avenge the murder of Yazdigird and Enthronement

Folio from a dispersed copy of Firdausi’s Shahnameh (Book of Kings)

- Accession Number:AKM37

- Place:Iran, Shiraz

- Dimensions:37 x 30.4 cm

- Date:741 AH /1341

- Materials and Technique:Ink, coloured pigments and gold on paper

Containing nearly 60,000 verses, the epic poem the Shahnameh by Firdausi recounts Iran’s mythical, legendary, and historical past from earliest times to the arrival of the Muslim Arabs in the mid-7th century AD. Near the epic’s conclusion, Firdausi recounts the events following King Yazdigird III’s abandonment by his own forces during a battle against an army of Turks. Yazdigird, the last legitimate ruler of Iran’s Sasanian dynasty, took refuge in a mill. There, he was killed through the treachery of Mahuy, who promptly assumed the Iranian throne. A powerful warrior named Bizhan, from the ancient city of Samarqand (in present-day Uzbekistan), learned of these events and set out with an army seeking revenge. Mahuy was quickly taken captive and brought before Bizhan. Fearful that he would be flayed alive, Mahuy implored Bizhan to cut off his head. Instead, Bizhan cut off Mahuy’s hands, feet, ears, and nose and paraded him around the camp on horseback. As a final coup de grâce, Bizhan ordered Mahuy and his three sons to be burned alive.

Further Reading

In AKM37 (folio 321 or 322 recto), the blood-red background of this illustration aptly conveys the violent climax of Firdausi’s epic poem. At the centre of the composition is the traitor Mahuy, who is being tortured for orchestrating King Yazdigird’s murder. Lying on the ground in front of Mahuy are his three sons, whose closed eyes indicate that they are already dead. All four of these ill-fated family members are dressed in prisoner garb: naked torsos and white trousers.

At the far right of the composition, the powerful warrior Bizhan (not the same Bizhan who kills Human in AKM33) directs Mahuy’s torture from a throne-like seat with the help of various soldiers and other assistants. The artist depicts Mahuy with his feet and hands missing; his torture and impending death are an explicit warning about the brutal repercussions of regicide.

This is the front (recto) side of the final text folio in the 1341 Shahnameh. It is no longer easy to determine the original folio number, here estimated at 321 or 322. At some point, the written and illustrated surface was remounted with a “fresh” margin (possibly from the same manuscript), bearing the number 58 in the upper right. In addition, a tear along the red column divider was repaired with small strips of thin paper. The other side of the folio is discussed as AKM37 (folio 321 or 322 verso).

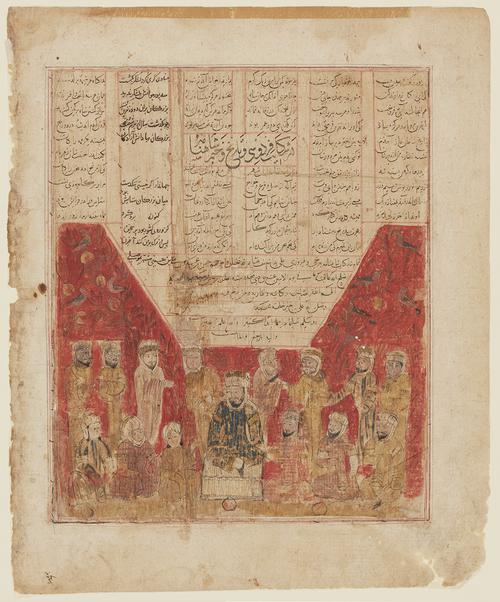

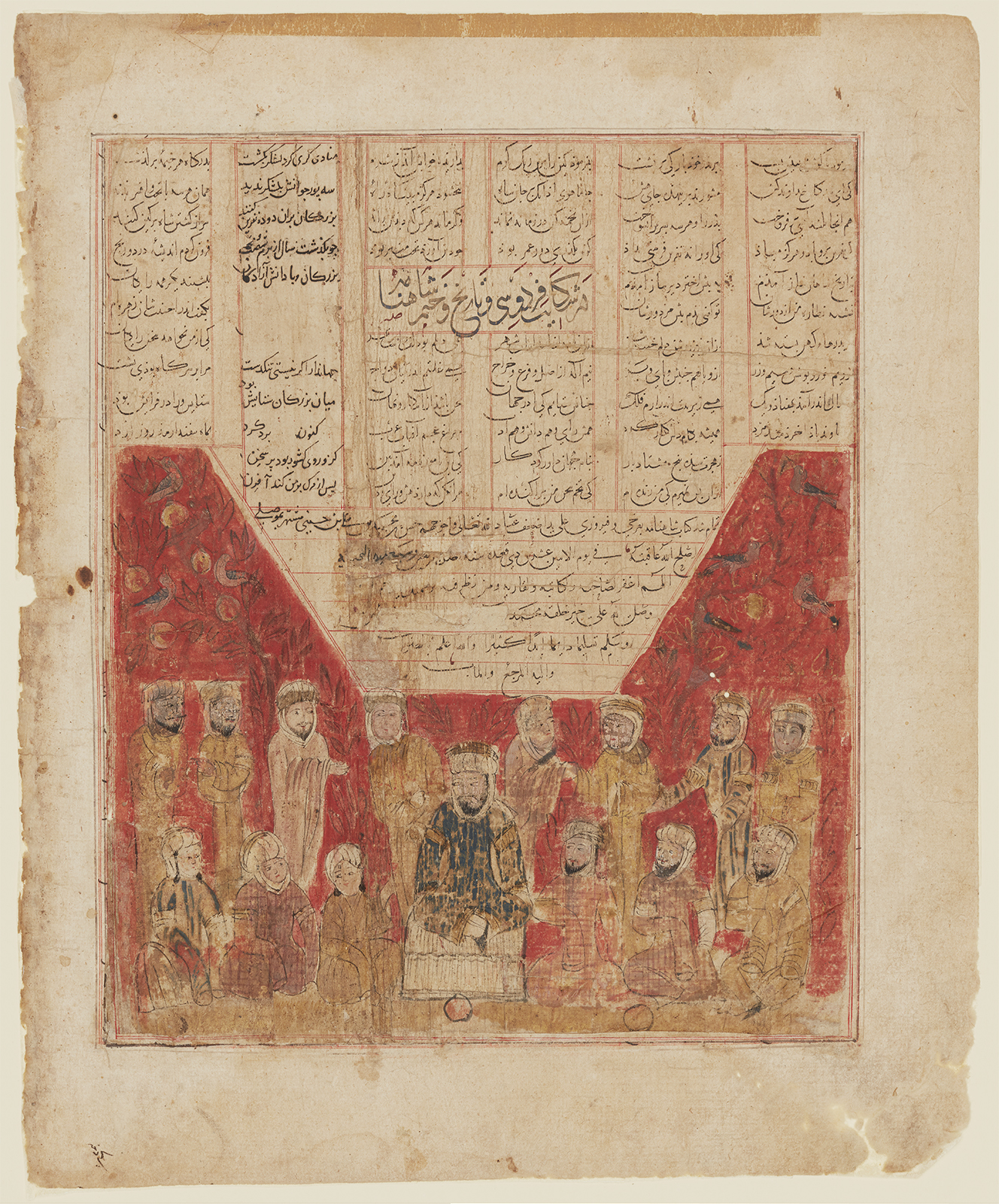

AKM37 (folio 321 or 322 verso), with its finispiece or closing composition presents the last verses of the Shahnameh (Book of Kings), the epic poem recounting Iran’s past from mythical times to the arrival of Muslim Arabs in the mid-7th century AD. Here, the poet Firdausi, now 71, describes his own challenges creating the Shahnameh over many years—and without sufficient monetary reward. He thanks an honourable man named Husayn Qotayb, who gave him food and comfort. He then concludes his poem with the date, corresponding to 8 March 1010 AD, and the following poetic flourish:

I’ve reached the end of this great history

And all the land will fill of talk of me;

I shall not die, these seeds I’ve sown will save

My name and reputation from the grave,

And men of sense and wisdom will proclaim,

When I have gone, my praises and my fame.

The connection between these verses and the enthronement scene at the bottom of the page is unclear. The illustration has generally been thought to represent Sultan Mahmud of Ghazna, who commissioned Firdausi (although apparently not generously) to compose the Shahnameh. Alternatively, it may represent Qiwam al-Dawla w’al-Din Hasan, the vizier (minister) who commissioned this 1341 version of the Shahnameh. It may even represent Firdausi himself, a suggestion that gains credence from the fact that the central figure is seated on a raised seat rather than on a throne and that he and the fourteen other seated and standing men wear turbans of the type seen in medieval Arab and Persian depictions of scholars. A final possibility is that the scene represents the coming of Islam to Iran. Firdausi does refer to the “era of Omar” following the long reign of traditional Persian monarchs that his tales celebrate, ending with the death of Yazdigird III.

Regardless of its intended reference, the illustration resembles other enthronement scenes produced during the period when native Iranian administrators, called Injus, ruled individual regions of the Mongol Empire (1206–1368). The scene is unusual, however, in that the enthronement is set outside, with numerous birds perching on the leafy branches of the trees that fill the twin triangular spaces above the figures’ heads. The somewhat hasty application of the red background also suggests that it has been repainted, along with some of the pointed black beards.

Six lines of prose text, framed in red horizontal lines and of descending width to form a trapezoid, follow Firdausi’s verses. This comprises the colophon, or scribal note, that documents the transcription of this particular copy of Firdausi’s poem. Although the colophon is badly damaged, and partly rewritten, enough of the original inscription remains to confirm that the manuscript was copied by the scribe Hasan ibn Muhammad ibn ‘Ali ibn Husayni, known as al-Mausili (meaning from the town of Mosul) and completed on the 20th day of the month of Dhu’l-Qada. Unfortunately, the year has been obliterated, but it has been generally assumed that it would have read 741, identifying the completion date of the volume as 7 May 1341.

— Marianna Shreve Simpson

Note: This online resource is reviewed and updated on an ongoing basis. We are committed to improving this information and will revise and update knowledge about this object as it becomes available.