Click on the image to zoom

Dala’il al-Khayrat Prayer book

- Accession Number:AKM535

- Place:North Africa, probably Morocco

- Dimensions:13.2 × 13.8 × 5.9 cm

- Date:19th century

- Materials and Technique:gilt and embossed leather binding; opaque watercolour, gold and ink on paper

By the time this prayer book known as Dala’il al-Khayrat [1] was created, its collection of prayers for the Prophet Muhammad had become the most copied religious and devotional text in Sunni Islam after the Qur’an. Carrying the Dala’il al-Khayrat and reciting its prayers were thought to provide blessing (baraka), good luck, and protection. Four centuries earlier, its text was composed in Morocco by the Moroccan sufi and mystic scholar Muhammad b. Sulayman al-Jazuli (d. 1465). The text gained popularity from the 16th century onward and spread throughout northern Africa, eventually making its way as far east as China.

Further Reading

This Dala’il manuscript is a particularly fine copy produced by the later North African school, which increasingly produced sophisticated examples in the 18th and 19th centuries. This devotional codex distinguishes itself through its many lavish illuminations and calligraphies, and its extensive use of gold paint to highlight the important words and illuminate its margins. It is also a good example of how the hierarchy of the layout and style of illumination can assist the reader not only in locating chapters and sections necessary for the recitation ritual, but also in distinguishing parts of the Prophet Muhammad, such as his names, genealogy, sandal, and rawdah the “blessed garden” in Medina where the Prophet and his companions are burried.

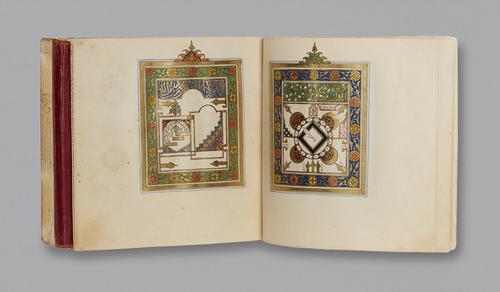

The manuscript is bound in a red morocco leather binding with a flap, and embossed with a gilt geometric interlacing star-design. Its green doublures are decorated with regular floral patterns within a scalloping grid. The text-block is decorated with a floral and calligraphic composition. The codex comprises 354 folios, with eleven lines of small and elegant maghribi script per page; 21 folios and three double-pages are lavishly illuminated. Fine red paper is inserted to protect the lavish illuminated pages. The work features many characteristics typical of the North African school of Dala’il al-Khayrat manuscript production. The overall square-like format of the manuscript—with pages designed as exact squares measuring 13.2 x 13.2 cm—is common in later North Africa Dala’ils. The rectangular horizontal field-design of the chapter headings and end marks extend into the margin with a narrow line and culminate in a distinct circular vignette (‘ansa) filled with stylized vegetal motif. Rooted in early Qur’an production from the late 7th and early 8th centuries, such “text-field” headings or end-marks include information about the previous or following section, and act as visual signs that facilitate navigation of the text and help locate a particular passage. [2]

Throughout the manuscript, backgrounds in larger panels, section headings or illustrations are coloured in red, blue, green, yellow and variations of purple, while the pattern and motifs of the decoration itself are drawn in gold and outlined in black. Small spiral-drop elements are placed between prayers and highlight names of the Prophet or religious words, probably a visual and stylistic way to signal the Epithet (or Eulogy) of the Prophet salla llahu ‘alaihi wa-sallam (May God bless him and give him Salvation). The application of gold outlined in black instead of the otherwise popular yellow, green, red, or blue also attests to the degree of luxuriousness of this manuscript. [3] Elegant thuluth is used throughout for decorative panels or in the text to further distinguish such important words and parts from the main text in magribi script.

The three double-pages are illustrated following the North African convention: first, a stylized image of the Prophet’s Sandal (fol. 16v), which forms a pointed arch on the left end and a floral motif on the right side. Paisley motifs, roundels, and palmettes decorate the composition, with two inscribed lines in the centre describing the honour of the Prophet.

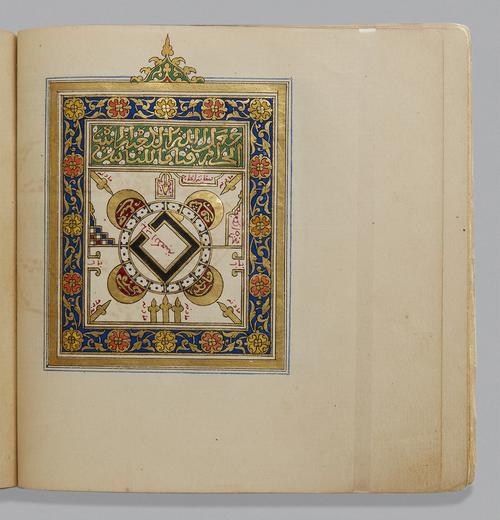

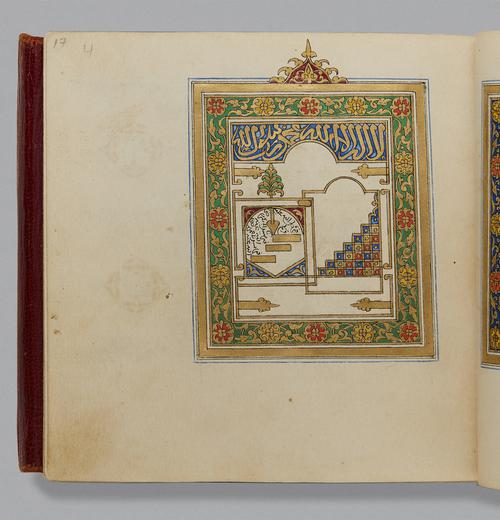

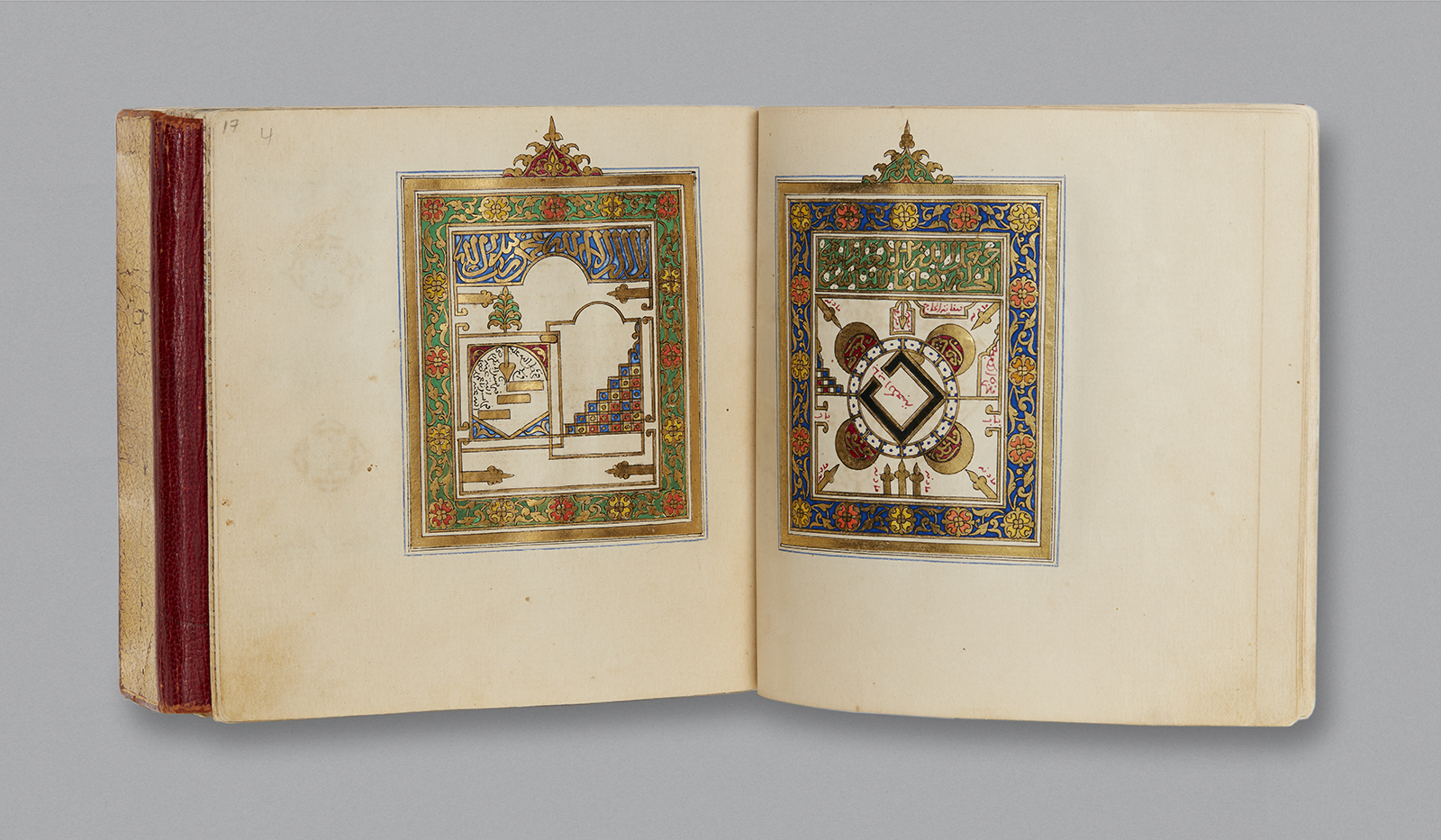

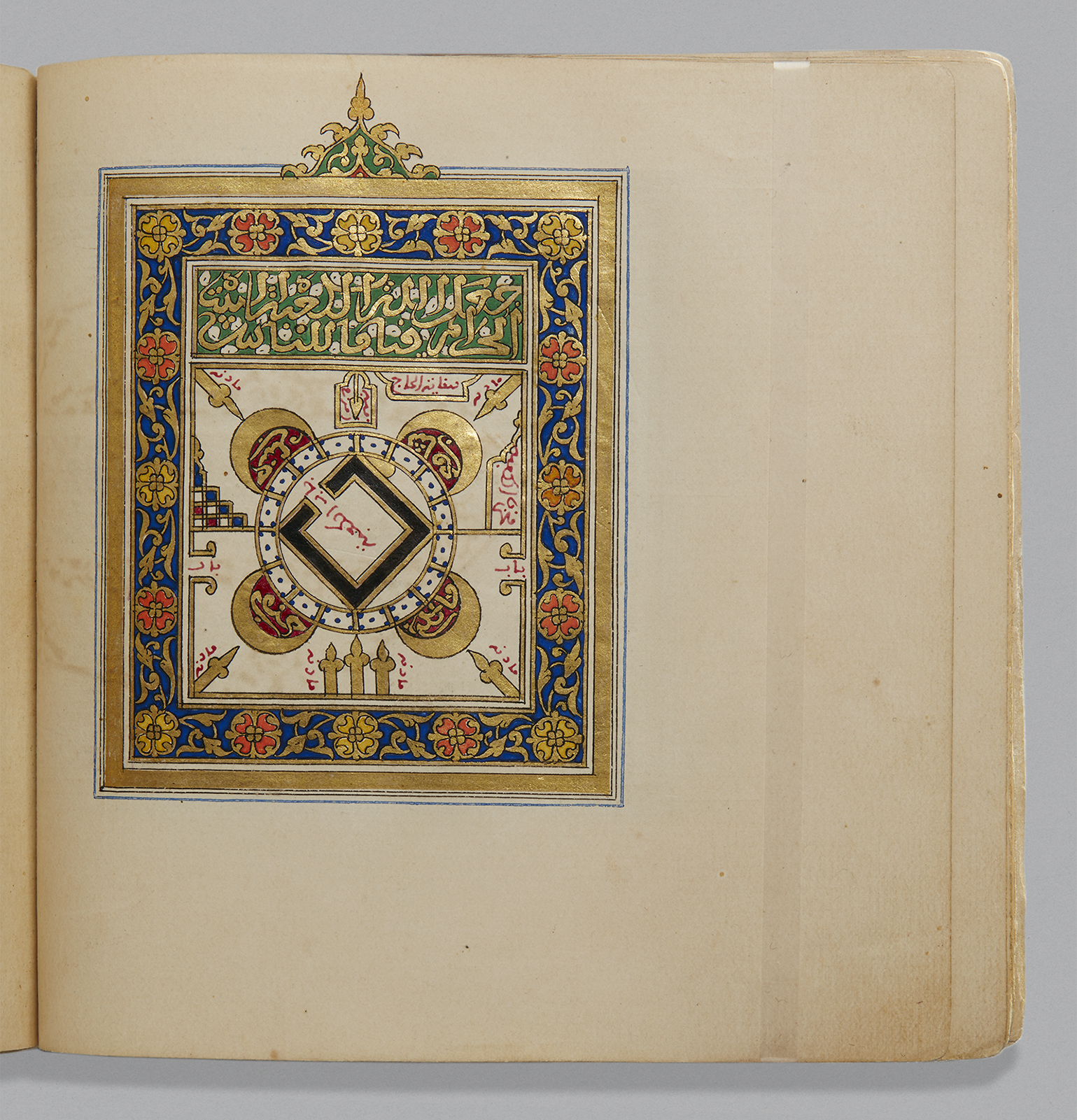

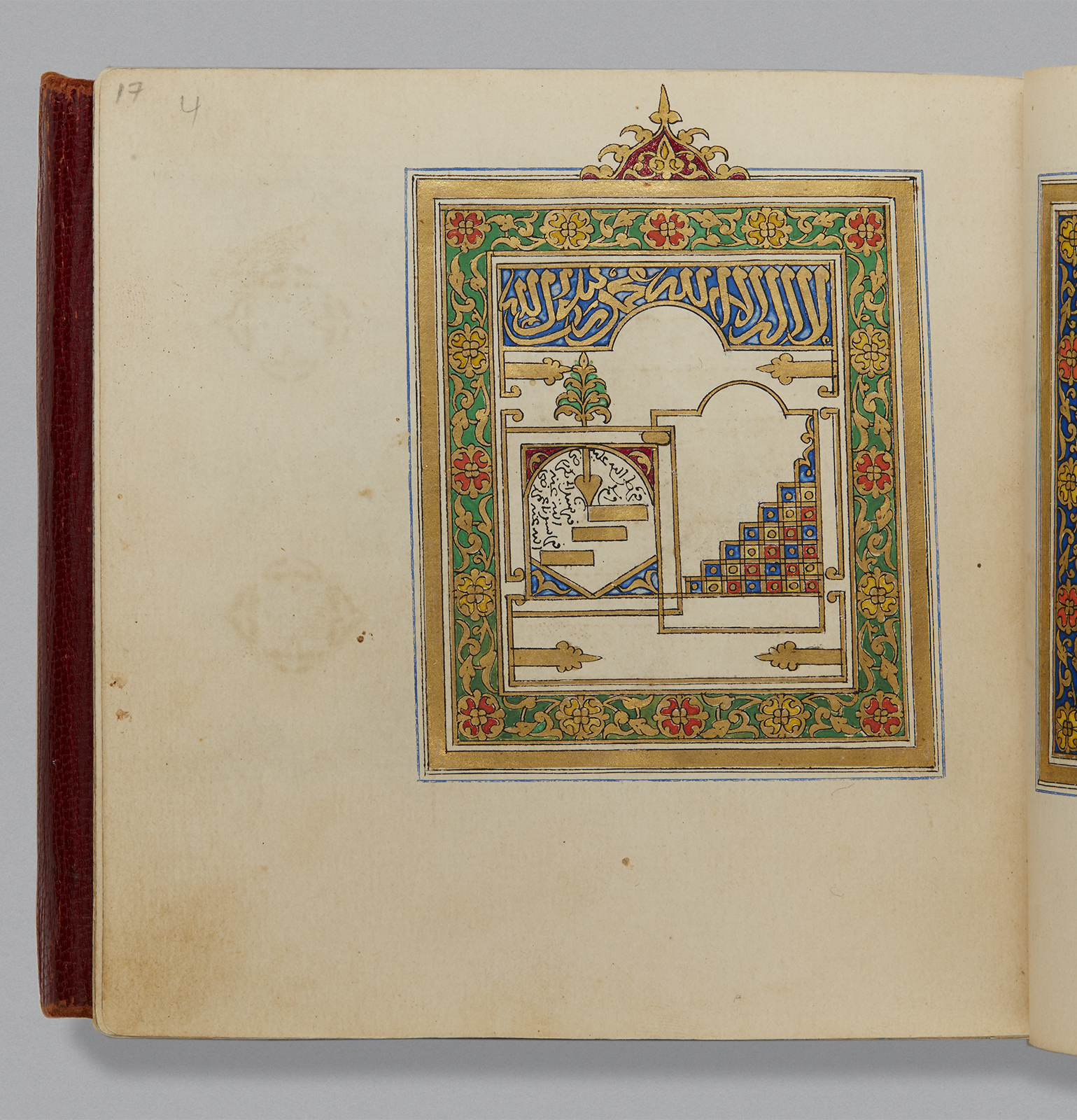

The following double-page depicts the two holy Muslim cities of Mecca on the right and Medina on the left (fol. 17r). These architectural images are two-dimensional and composed in a concentric manner. The rectangular Ka‘ba occupies the centre, the four maqams or pavilions representing the four legal schools of Islam are drawn as crescent moons—a common motif in Moroccan art. Medina is depicted with the minbar or pulpit of the Great Mosque, drawn as a staircase, on the right side, and on the left are three staggered rectangles framed within an arched window-like scheme. This is an illustration of al-Jazuli’s description of the “blessed garden” in Medina with the coffins or burials of the Prophet Muhammad and his two companions Abu Bakr and ‘Umar. The combination of the minbar and the Prophet’s tomb symbolizes the rawdah in Paradise, quoted in well-known prophetic traditions, “whatever is between my grave and my pulpit, is one of the gardens of Paradise.” [4]

Typical for North African copies, the same combination appears again following the description in the text, but developing on an elaborate illuminated double-page (fol. 33). The composition is shown as a close-up (and not as a bird’s-eye view applied in the Mecca image), the three coffins on the right and the minbar on the left, each page designed as an arched niche evoking the mihrab. The passage in the text referring to the blessed garden is presented as an illuminated calligraphic panel (fol. 32). It is one of the many passages relating to the Prophet, which in this copy are rendered in a highly sophisticated style. These passages and illustrations add to the luxuriousness of the book as a whole. See AKM382, AKM535 and AKM278 for examples of Dala’il al-Khayrat prayer books in the Aga Khan Museum Collection.

— Deniz Beyazit

Notes

[1] The full title is Dala’il al-Khayrat wa Shawariq al-Anwar fi Dhikr al-Salat ‘ala al-Nabi al-Mukhtar (Translation from Witkam 2007, 69: “Guidelines to the Blessing and the Shinings of Lights, Giving the Saying of the blessing prayer over the Chosen Prophet”).

[2] On layout characteristics of the individual schools for Dala’il al-Khayrat manuscripts, see Daub 2016, 133–170.

[3] Daub 2016, 151–58; Daiber 2011, 12.

[4] Witkam 2007, 72–3.

References

Aga Khan Trust for Culture. Masterpieces of Islamic Art: Treasures of the Aga Khan Museum. Geneva: Aga Khan Trust for Culture, 2010. ISBN: 9783894796037

Daiber, Verena. Die Handschriften im Universitätsmuseum Islamische Kunst. Bamberg: The Bumiller Collection, 2011. ISBN 978-3-9523871-1-5

Daub, Frederike-Wiebke. Formen und Funktionen des Layouts in arabischen Manuskription anhand von Abschriften religöser Texte Burda, al-Ğazūlīs Dalā’il und die Šifā’ von Qādī ‘Iyād (Arabische Studien 12). Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2016. ISBN: 9783447106702

Witkam, Jan Just. “The battle of the images: Mekka vs. Medina in the iconography of the manuscripts of al-Jazuli’s Dala’il al-Khayrat.” In Pfeiffer, Judith and Manfred Kropp, Theoretical Approaches to the Transmission and Edition of Oriental Manuscripts, Proceedings of a symposium held in Istanbul March 28-30, 2001. Beirut: Ergon Verlag, 2007, 67–82. ISBN: 9783899135329

Note: This online resource is reviewed and updated on an ongoing basis. We are committed to improving this information and will revise and update knowledge about this object as it becomes available.