Click on the image to zoom

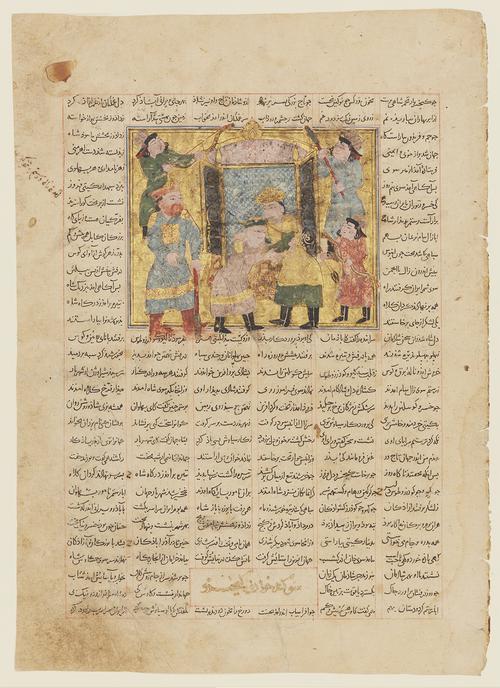

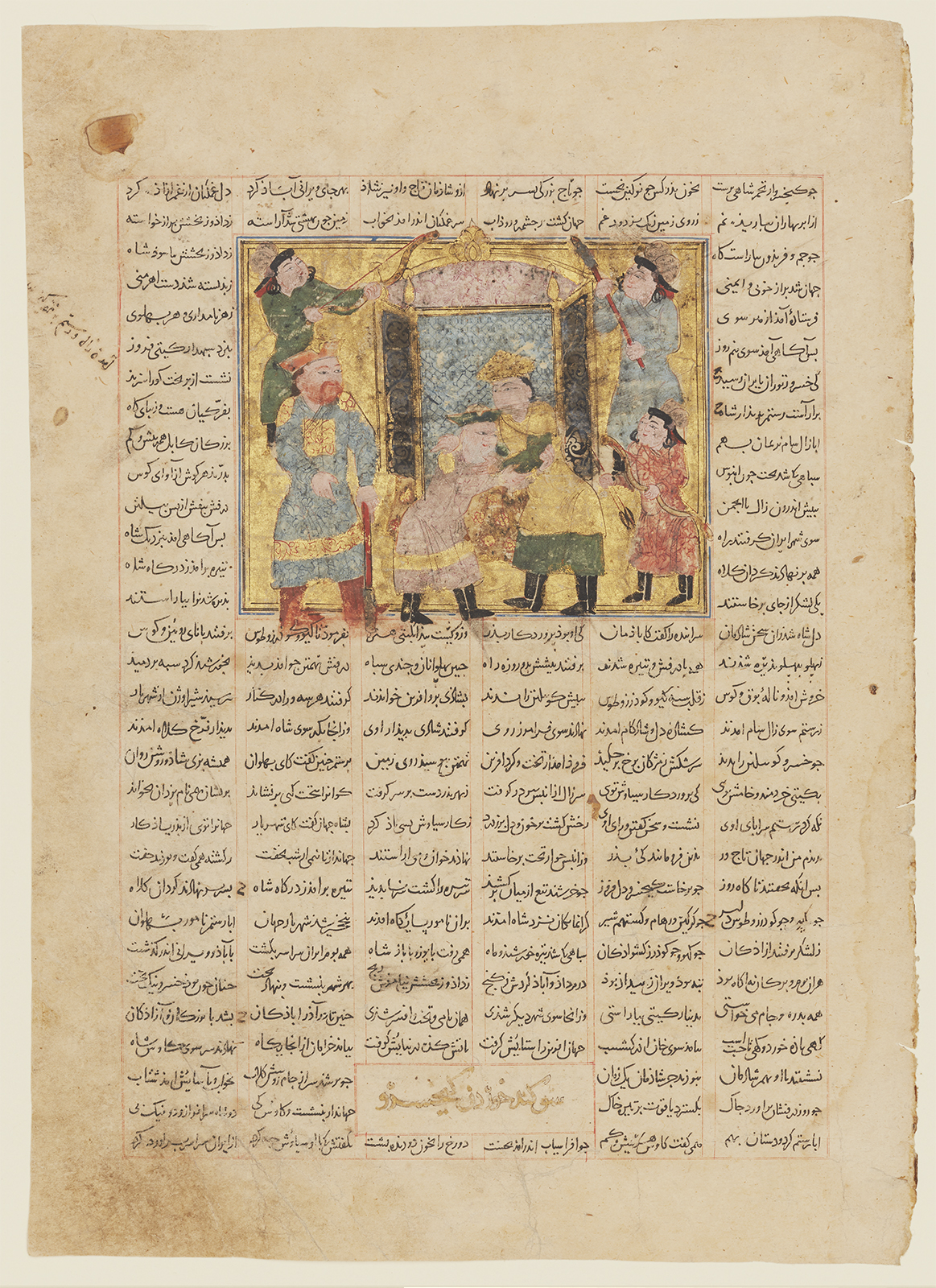

Kay Khusrau Swears Vengeance toward Afrasiyab before his Grandfather, Kay Kavus

Folio from a dispersed copy of Firdausi’s Shahnameh (Book of Kings)

- Accession Number:AKM22

- Place:Western Iran

- Dimensions:30.8 x 22 cm

- Date:late 13th or early 14th century

- Materials and Technique:ink, opaque watercolour, gold, and silver on paper

The painting on this folio from the dispersed copy of the “Freer” Shahnameh (Book of Kings), along with another folio from this Shahnameh (AKM84), illustrates a story of one of the legendary kings of pre-Islamic Persia.

Six persons and a simple setting are the components of this picture. Together, they convey an occasion of much import within the larger framework of Firdausi’s Shahnameh: the young Khusrau, son of Siyavush, swears to avenge the murder of his father by Afrasiyab. He also pledges to remain true to his Iranian heritage, advancing the Iranian cause in the continuing “Great War” between Iran and Turan, the land of the Turks (for Firdausi, east of the Oxus River). In Firdausi’s verse, the hero Rustam and his father Zal are present at the momentous discussion, and Rustam is given Khusrau’s oath, written in Pahlavi script on parchment, for safekeeping. Interestingly, however, in this painting neither the older man being greeted by the young crowned king nor any of the four attendants, seems to resemble the white-haired Zal or his son Rustam, who is usually recognizable by his tiger-skin tunic (see AKM18).

See AKM20 for an introduction to the “Freer” Shahnameh.

Further Reading

The background to the moment actually depicted here—a son’s determination to avenge the murder of his father—is dramatic and complex: Sudabah, young wife of Kay Kavus, grandfather to Kay Khusrau, had conceived a dangerous passion for Siyavush, her stepson and crown prince but, being rebuffed, falsely accused him to his father. Siyavush submitted—successfully—to trial by fire, emerging unscathed and arguing with his father for his stepmother’s life but, in time, her passion for the youth was re-ignited.

At the same time, Turan, under the rule and command of Afrasiyab, the Turanian ruler, again began to menace Iran; Siyavush stepped forth, ready to lead the Iranian forces against the Turanians, at the same time freeing himself from Sudabah’s repeated advances. Armed and accompanied by the great hero Rustam, Siyavush was ready to attack the Turanian forces before the city of Balkh, but Afrasiyab had a terrible dream—that he would be slain by a youthful Iranian king. He thus proposed peace with Siyavush. Letters flew back and forth between the court and its warriors, far out on the eastern border between Iran and Turan: Siyavush had effectively accomplished his father’s aim—but by making peace, not destructive war. Accusations abounded and emotion ran high; Siyavush, feeling gravely ill-used, eventually accepted the offer of Afrasiyab to reside at his court. The Turk observed that Kavus was wanting in wisdom if he could give up so noble a son possessed of such farr.[1]

When Siyavush wished to marry Farangis, one of Afrasiyab’s daughters, the import of the awful dream returned. Shortly after his son, Kay Khusrau, was born, Siyavush was murdered at the instigation of his father-in-law, Afrasiyab. Looked after by the Turanian courtier Piran, the child was hidden for safekeeping and, later, protected by the ruse of appearing half-witted; this despite the fact that, his lineage was royal on both sides, Iranian and Turanian, and his kingly farr recognized: “Lineage and skill won’t stay hidden long.” Sought for seven years, he was eventually found by Giv, son of the faithful Iranian courtier, “Old Gudarz.” With his mother Farangis, the three recrossed the Oxus River into Iranian lands and arrived at court. His grandfather Kay Kavus welcomed Kay Khusrau joyously and abdicated in his favour.

This painting—and indeed Firdausi’s verse—affirm that Khusrau possesses farr, one of the fundamental features of legitimate kingship that embodies glory and personal charisma and is sometimes also understood as a mystical power bestowed by divine selection. Wearing a gold crown, Kay Khusrau embraces an older man who is uncrowned but is probably intended to be his grandfather Kay Kavus. A painting of the same episode from the “First Small” Shahnameh [2] shows the same pair of figures in reverse; but both are crowned, leaving no doubt that they are meant to be Kay Kavus and his ruling grandson, Kay Khusrau.

The Aga Khan Museum Collection has four folios from the “Freer” Shahnameh, AKM20, AKM21, AKM22 and AKM84.

Notes

[1] Farr is Zoroastrian in concept and derives, linguistically, from the language of the Avesta (or Zand-Avesta), the Zoroastrian scripture: khvarenah or khwarenah (in Avestan, xᵛarənah). The word, and its significance, resonate throughout Firdausi’s epic: true kings have it, even when they are not accorded their true rank. Farr is evident to others, even in the most apparently humble of persons; those who falsely lay claim to the throne are perceived to lack farr and never achieve their aims. Moreover, kings who do not behave rightly or abuse their power may lose their farr and their position—sometimes, also, their lives. On farr, see the entry in the Encyclopedia Iranica: FARR(AH).

[2] Dublin, Chester Beatty Library, Per 104, folio 16r; Simpson 1979, 386 (the episode is somewhat differently entitled).

Note: This online resource is reviewed and updated on an ongoing basis. We are committed to improving this information and will revise and update knowledge about this object as it becomes available.