Click on the image to zoom

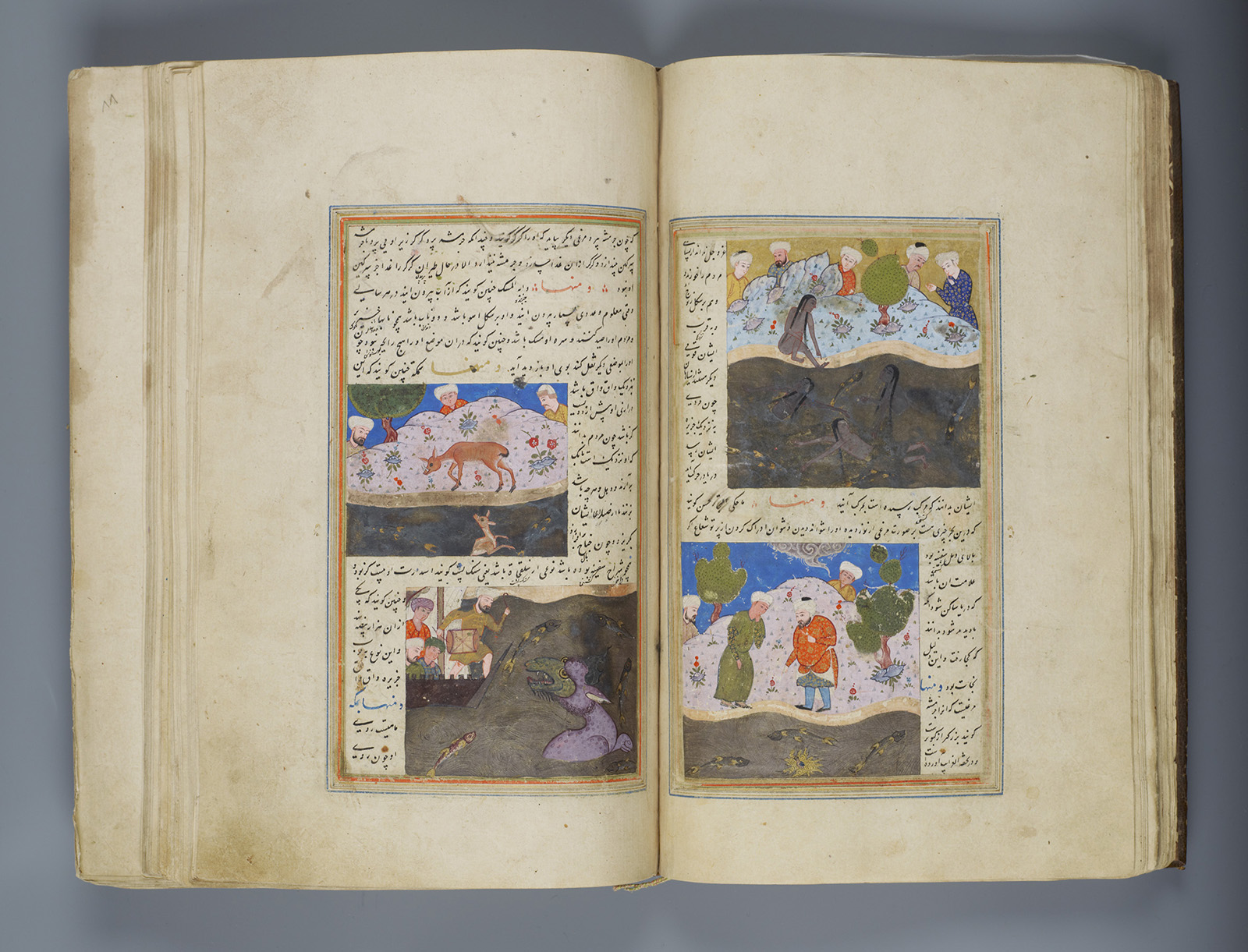

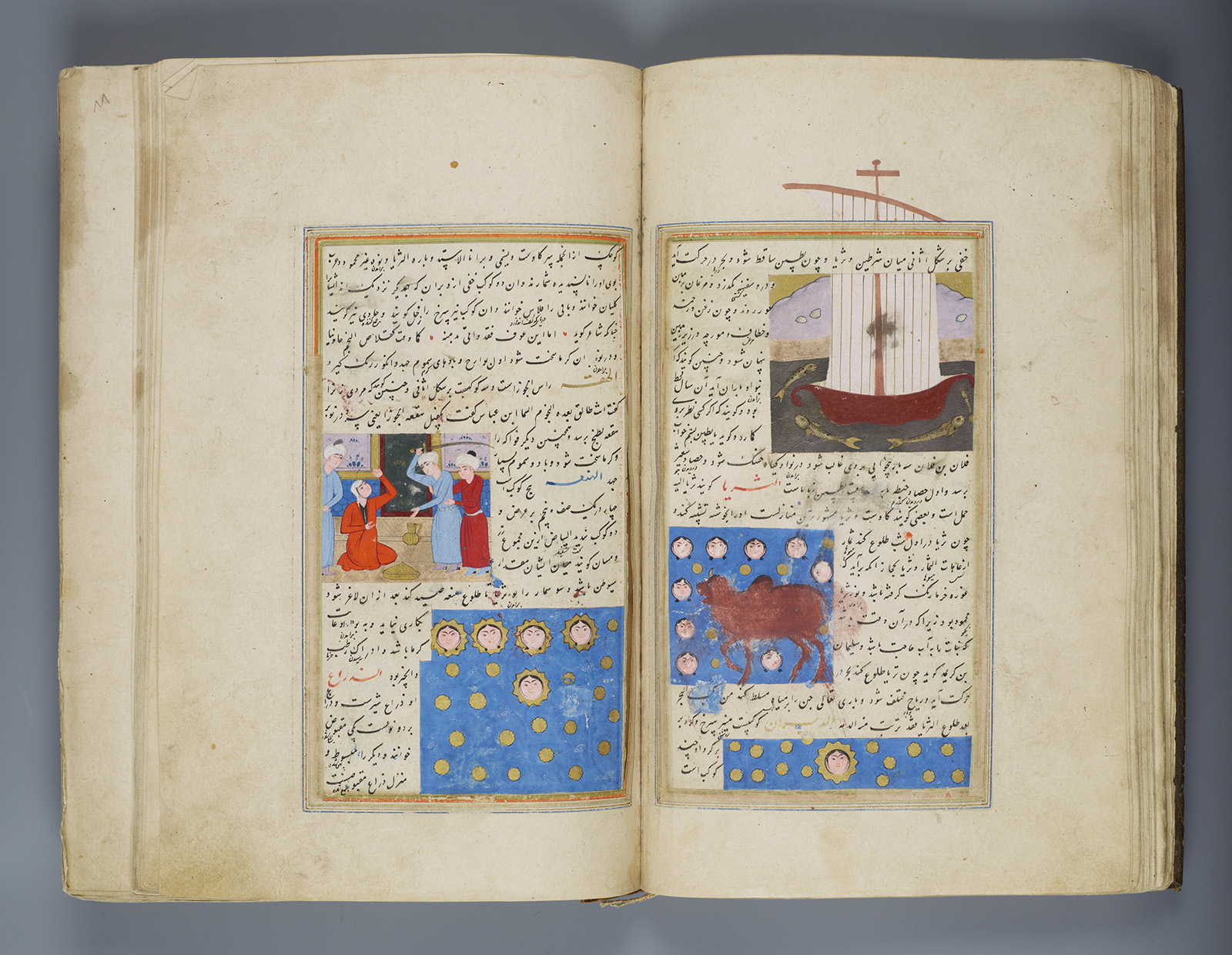

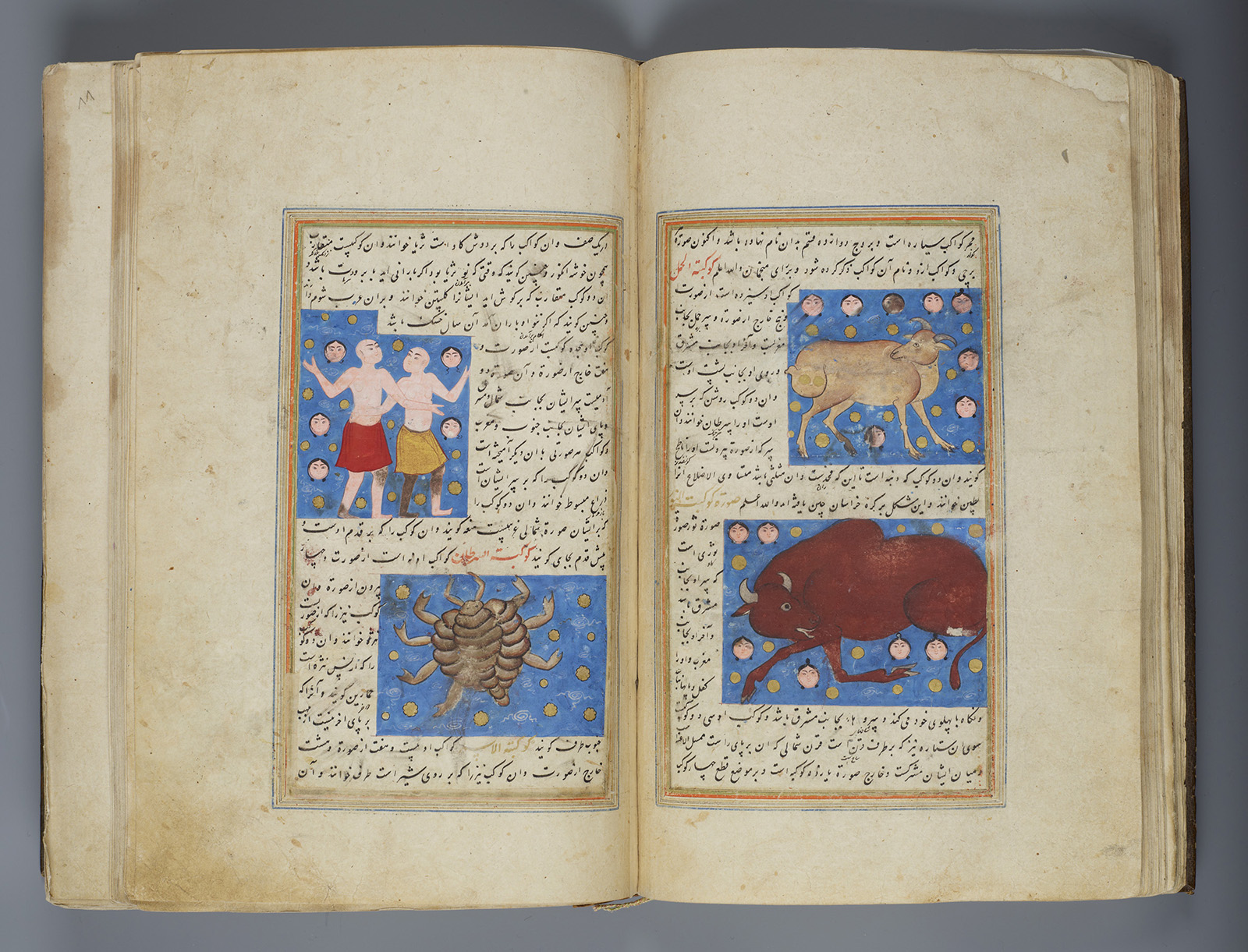

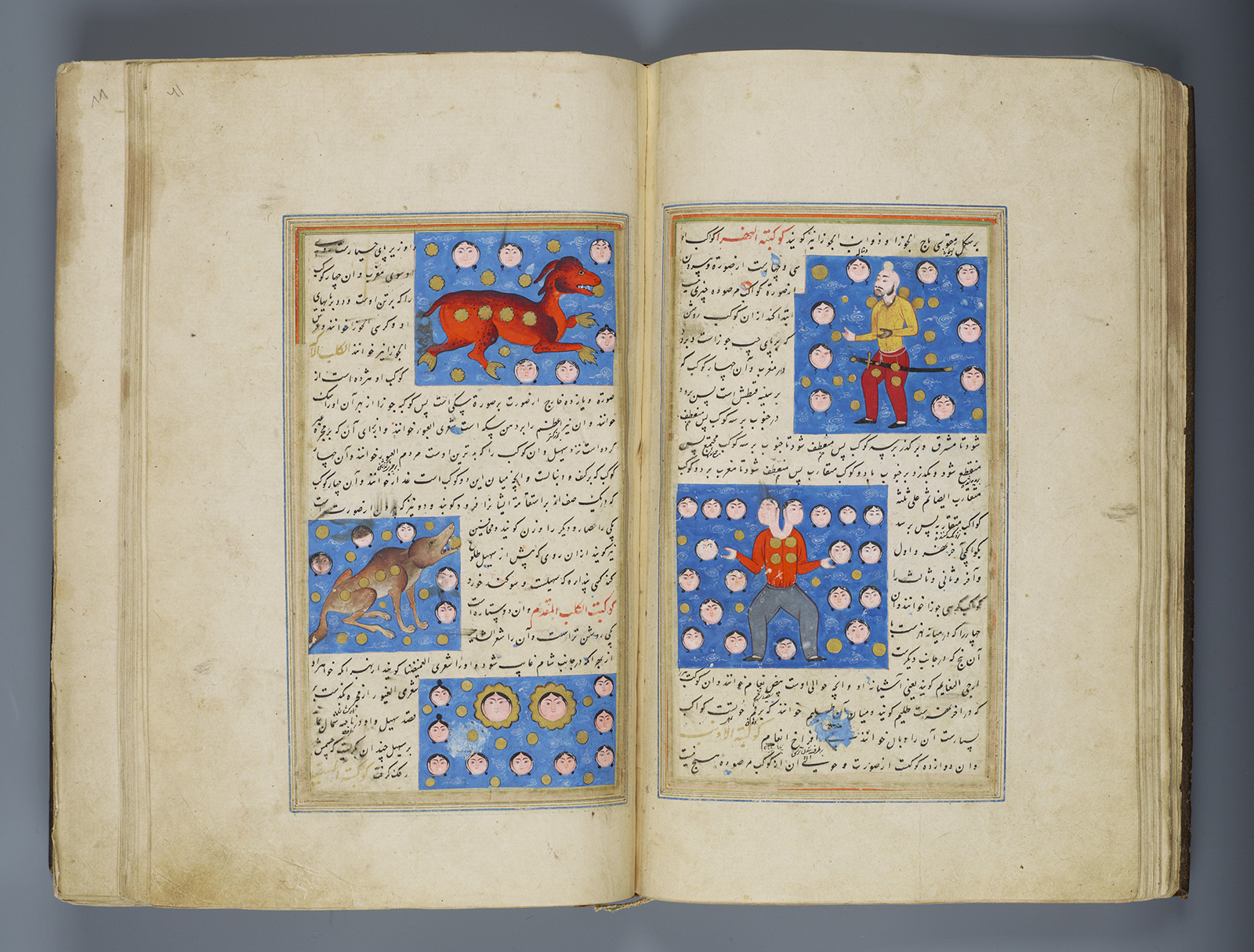

Manuscript of The Wonders of Creation and the Oddities of What Exists (Ajayeb al-Makhluqat va Gharayeb al-Mowjudat)

- Accession Number:AKM367

- Creator:Zakariya’ b. Muhammad al-Qazwini (d. 682/1283)

- Place:Iran, Shiraz

- Dimensions:26.6 x 17.6 x 4 cm

- Date:partly copied in later 15th century and completed ca. 1570

- Materials and Technique:ink, opaque water colour and gold on paper, gilt-stamped brown morocco binding

Composed by Zakariya’ al-Qazwini in several Persian and Arabic versions in the years following the Mongol conquest of Baghdad (656/1258), ‘Aja’ib al-makhluqat wa-ghara’ib al-mawjudat (The Wonders of Creation and the Oddities of Existing Things) became the most popular medieval encyclopaedia of natural history. The author declared his aim to help the reader understand the omnipotence and benevolence of God by encouraging him to marvel at the astonishing variety of creation and the amazing perfectness of all its components, both heavenly and earthly.

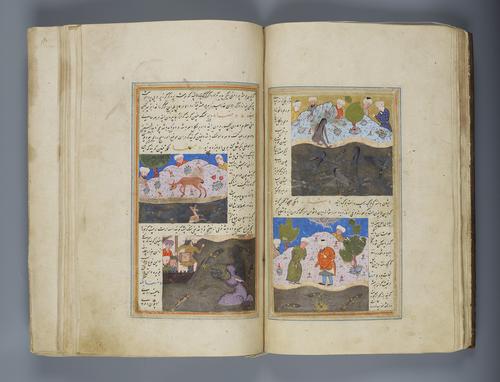

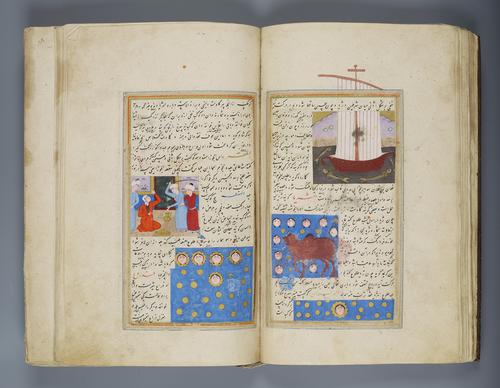

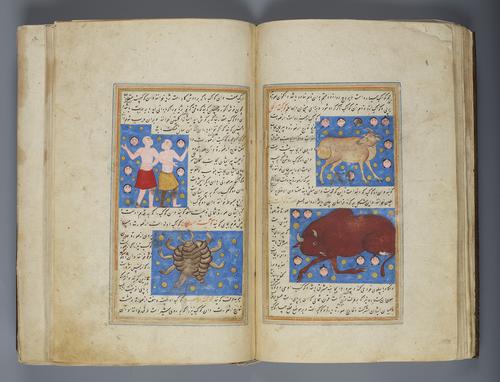

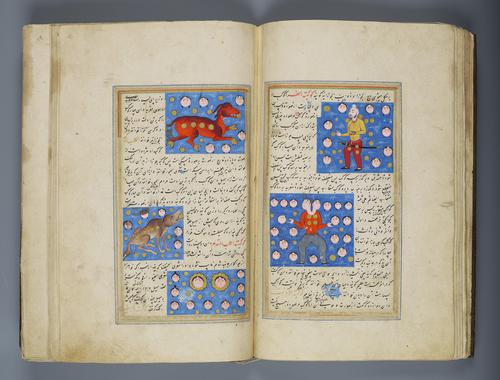

When copied, Qazwini’s work was often provided with thorough diagrams and figural illustrations. Whereas early copies supplemented the verbal description with a mere visual representation of objects, copies created in the second half of the 16th century frequently included spectators responding in various ways to what they observed. These later copies directed the reader’s attention as much to the act of marvelling on creation as to the curious object itself. Dated to approximately 1570, the manuscript in the Aga Khan Museum Collection falls into the latter group.[1]

Further Reading

In the first of two maqalas (discourses), Qazwini speaks about the planets, the constellations, the angels, and the calendars of various communities. In the second maqala, he describes the sublunary spheres of fire, air (weather phenomena), water (the seven seas with their islands and the creatures inhabiting them and the surrounding water), and earth (mentioning a number of mountains, rivers, springs and wells). Another part of this maqala is dedicated to the “generated beings” (ka’inat): minerals, plants and living beings, including humans. Qazwini describes the beings’ “occult qualities,” and suggests how readers can use them to their advantage. The book concludes with a chapter on strange creatures.

The manuscript AKM367 contains the Persian version that had been completed in 659/1260-61, according to the earliest known manuscript preserved in the Süleymaniye Library. [2] It has an extended chapter on the human being that is lacking in later versions; this chapter details the characteristics of various peoples and the wonders of arts and crafts. Nothing is known about its dedicatee (a certain Shahpur b. ‘Uthman), but an Arabic version (completed in 661/1262-63 [3]) was dedicated to the governor of Baghdad ‘Ala’ al-Din ‘Ata-Malik al-Juwayni (d. 681/1283).

The first Persian version gained in popularity after the mid-15th century. The main production centre of illustrated ‘Aja’ib al-makhluqat was Shiraz, home to numerous commercial workshops. The style of the miniatures in AKM 367 allows a definite attribution to a Shiraz atelier about 1570, notwithstanding the colophon date 899/1493-94. However, both facts cannot be reconciled by assuming that the copy had been left unfinished for about 80 years until the miniatures were executed because of a peculiarity in the layout of many illustrated pages: the placement of small miniatures in the middle of the written surface thus interrupting several lines of writing. This kind of layout was only introduced by Shiraz workshops after the middle of the 16th century.[4] That the whole manuscript was made then is contradicted by the uncommonly large number of lines (21) per page and the measurements of the written surface which would better fit an earlier date.[5] This fact leads to the suggestion that fragments of an unfinished manuscript were completed about 1570 by painting in the left-empty spaces and replacing lost folios.[6] Differences in writing seem to support this assumption.[7]

The pictorial program of AKM367 differs from other copies illustrated in Shiraz workshops in the second half of the 16th century. It dispenses completely with diagrams that served as visual explanations of the orbits of the planets, including eclipses and magical squares. Wherever possible, the introduction of curious humans compensates for this loss of information. The pictorial program obviously cherishes opportunities to show people wondering: watching an animal, pointing it out to others, discussing it or making use of it. The human being marvelling on natural phenomena is as much the topic of these illustrations as the object described in the respective entry. In this way, the miniatures support Qazwini’s invitation to the reader to meditate on the wonders of creation.

— Karin Ruehrdanz

Notes

[1] The manuscript lost a considerable number of leaves, in particular in those chapters that had been heavily illustrated. While such losses are obvious other gaps are more difficult to identify. The repair must have been based upon a defect model. The calligrapher covered such gaps by continuous writing thus merging different entries and even chapters. Further confusion was created by the person (usually the illuminator) responsible for writing the headlines in the spaces that had been left for this purpose. Despite the problems this created for the reader the book was used and carefully read as glosses and explanations later written between the lines or at the margin prove.)

[2] Ms Fatih 4174 includes the year of completion in the inscription on fol. 1a. It is corroborated by internal evidence: the year 658/1259-60 is mentioned as the current year in the first maqala.

[3] This is the year named as “current” in the first Arabic version, as for instance in Berlin State Library, or. fol.81, and Leipzig University Library, DC 2. For the earliest known illustrated but only fragmentarily preserved manuscript of that version, see Stefano Carboni, The Wonders of Creation and the Singularities of Painting: A Study of the Ilkhanid London Qazvīnī (Edinburgh, 2015), ISBN: 9780748683246.

[4] Based upon comparison of late 15th-century Shiraz copies like BnF suppl. pers. 1781, suppl. pers. 2051, Bodleian Library Laud Or. 132, Royal Asiatic Library Ms 178, Austrian National Library N.F. 155, with later 16th-century Shiraz copies TSM H. 403 and H. 407, and in particular a with leaves from a dispersed manuscript. For the latter, see for instance the exhibition catalogue L’Etrange et le Merveilleux en terres d’Islam (Paris: Louvre, 2001), nos. 37-42. ISBN: 9782711842155.

[5] Approximately 240 folios, 26.8 x 16.8 cm; written surface: 17.8 x 9.8 cm, 21 lines per page; 228 miniatures

[6] In such a case the calligrapher(s) would likely keep to the same number of lines per page as in the fragments.

[7] At the beginning the writing is narrower whereas later, at most pages, the width of some letters or connections between letters is stressed. That this kind of writing also appears on the colophon page may be explained by rewriting this page.

Note: This online resource is reviewed and updated on an ongoing basis. We are committed to improving this information and will revise and update knowledge about this object as it becomes available.