Click on the image to zoom

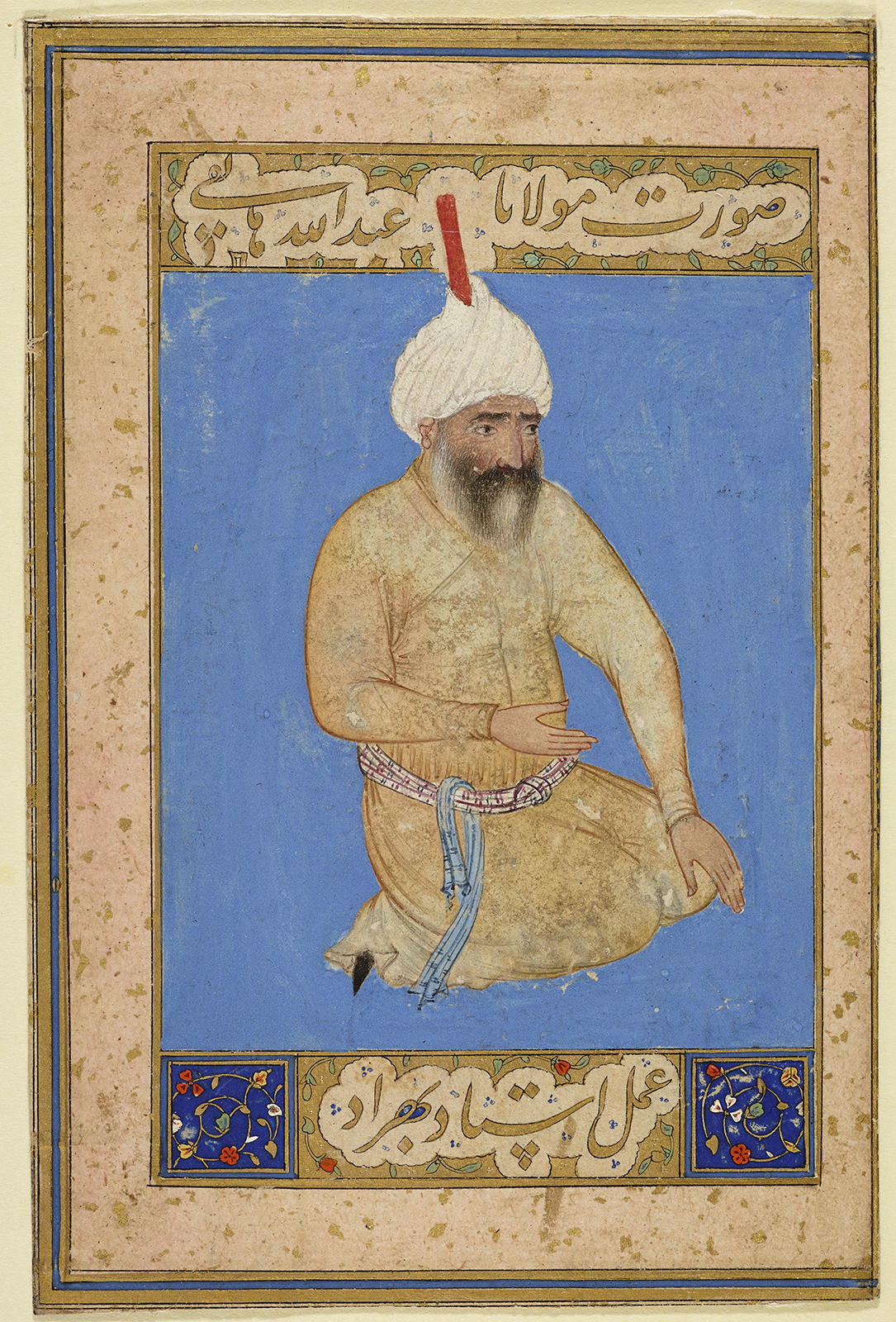

Portrait of Hatefi the Poet

Folio from a 1544–45 album assembled for Bahram Mirza

- Accession Number:AKM160

- Creator:Attributed to Behzad

- Place:Afghanistan, Herat

- Dimensions:11.8 x 7.8 cm

- Date:ca. 1511

- Materials and Technique:Opaque watercolour, ink, and gold on paper

This portrait depicts Hatifi, poet and nephew of the famous mystical poet Abd al-Rahman Jami, residing at the Herat-based court of late 15th-century Timurid ruler Sultan Hosayn Bayqara (r. 1470–1506).[1] This small painting was once part of a folio mounted in the same royal album and in the same folio as the drawing Two Caracals and Two Deer (AKM95), which was ordered by Bahram Mirza, brother of Shah Tahmasp I, the second ruler of the Safavid dynasty. The decision to include this tiny painting in the royal muraqqa‘ (album) was made by calligrapher and artist Dust Muhammad, who completed the album in 1544–45.[2] The attribution above the portrait simply states, “Depiction of Maw-lana Abd Allah Hatefi,” and below, “the work of Master Behzad.” [3] Through this attribution we have evidence of the portrait subject and the artist and can associate the drawing with Herat,[4] despite the fact that this information was added later, probably by Dust Muhammad.

Further Reading

One of Hatifi’s famous works is the historical epic Timur-Nameh (Book of Timur), in which he transformed the warlord Timur into a legendary Iranian hero. [5] At the time of his death in 1520, Hatifi was working on the Isma‘il-Nameh (Book of Isma’il), another ambitious epic which was to recount the life, exploits, and victories of Shah Isma‘il I.

In this portrait, Hatifi’s turban, with its long red taj (taj-e haydari) or baton,[6] is of Safavid design, proclaiming the poet’s allegiance to this Shia dynasty. This detail also suggests that the painting was made after Shah Isma‘il’s conquest of Herat and Khorasan Province in 1511. Moreover, it shows the delicacy of Bihzad, who created an homage to this historical meeting between the poet, a Shia devotee, and the ruler.

This masterful drawing demonstrates Bihzad’s gifts as a mature and insightful portraitist. Hatifi’s face, his hands, and their agitation are especially expressive. Such expressiveness is a hallmark of Bihzad’s skill in rendering such features. Their remarkable liveliness is a fine detail in the painting as are Hatifi’s greying beard and the intense expression on his lined face.[7] Bihzad’s style of painting, which was developed in Herat, was important and distinctive in its original compositions, modulated colours, naturalism, individualization of human figures and their interactions, and greater interest in genre detail.[8] When the Herat-born Bihzad joined the court of Shah Tahmasp at Tabriz,[9] Safavid court painting achieved a new synthesis, fusing elements of Turcoman painting with the Timurid style.

— Filiz Çakır Phillip

Notes

[1] David J. Roxburgh, “Disorderly Conduct?: F.R. Martin and the Bahram Mirza Album,” 49.

[2] Anthony Welch and Stuart Cary Welch, Arts of the Islamic Book: The Collection of Prince Sadruddin Aga Khan (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1982), 67.

[3] Thomas W. Lentz and Glenn D. Lowry, Timur and the Princely Vision: Persian Art and Culture in the Fifteenth Century (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1989), 361; Sheila R. Canby, Princes, Poets & Paladins: Islamic and Indian Paintings from the Collection of Prince and Princess Sadruddin Aga Khan (London: Trustees of the British Museum, 1998), 42.

[4] Adel Adamova, Mediaeval Persian Painting: The Evolution of an Artistic Vision, trans. J.M. Rogers (New York: Bibliotheca Persica, 2008), 53.

[5] Lentz and Lowry, 361.

[6] Michele Bernardini, Abdallah Hatefi. I sette scenari (Naples: Istituto Universitario Orientale, Dipartimento di Studi Asiatici, Series Minor 46, 1995), 52.

[7] Lentz and Lowry, 361; Welch and Welch, 69.

[8] Carey.

[9] V. Minorsky, trans., Calligraphers and Painters: A Treatise by Qadi Ahmad, Son of Mir-Munshi, 181.

References

Adamova, Adel. Mediaeval Persian Painting: The Evolution of an Artistic Vision. Trans. J.M. Rogers. New York: Bibliotheca Persica, 2008. ISBN: 9781934283059

Bernardini, Michele. Abdallah Hatefi. I sette scenari. Naples: Istituto Universitario Orientale Dipartimento di Studi Asiatici, Series Minor 46 (1995). http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/36785350

Canby, Sheila. Princes, Poets & Paladins: Islamic and Indian Paintings from the Collection of Prince and Princess Sadruddin Aga Khan. London: Trustees of the British Museum, 1998. ISBN: 9780714114835

Carey, Moya. “Prince and Princess Sadruddin Aga Khan Collection of Islamic Art.” Unpublished manuscript. London, 2002.

Lentz, Thomas W., and Glenn D. Lowry. Timur and the Princely Vision: Persian Art and Culture in the Fifteenth Century. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1989. ISBN: 9780874747065

Minorsky, V., trans. Calligraphers and Painters: A Treatise by Qadi Ahmad, Son of Mir-Munshi. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1959. https://doi.org/10.1163/19606028_027_01-25

Phillip, Filiz Çakır. Enchanted lines: drawings from the Aga Khan Museum collection. 2014. ISBN: 9780991992874

Roxburgh, David J. “Disorderly Conduct?: F.R. Martin and the Bahram Mirza Album.” Muqarnas 15 (1998): 32–57. ISBN: 9789004110847

Welch, Anthony, and Stuart Cary Welch. Arts of the Islamic Book: The Collection of Prince Sadruddin Aga Khan. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1982.

Note: This online resource is reviewed and updated on an ongoing basis. We are committed to improving this information and will revise and update knowledge about this object as it becomes available.