Click on the image to zoom

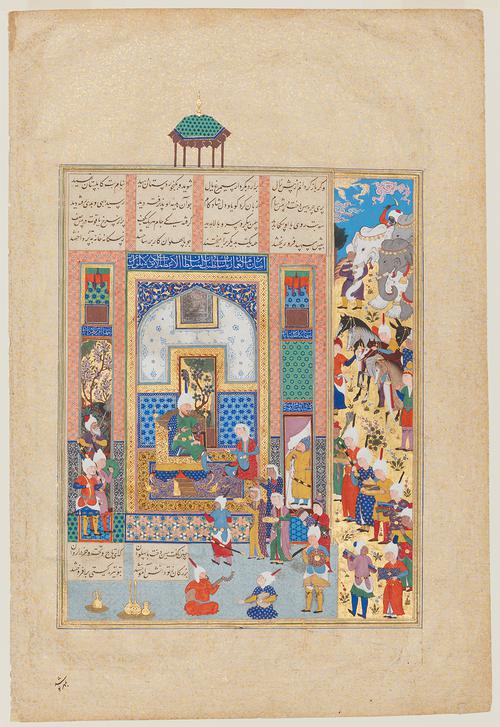

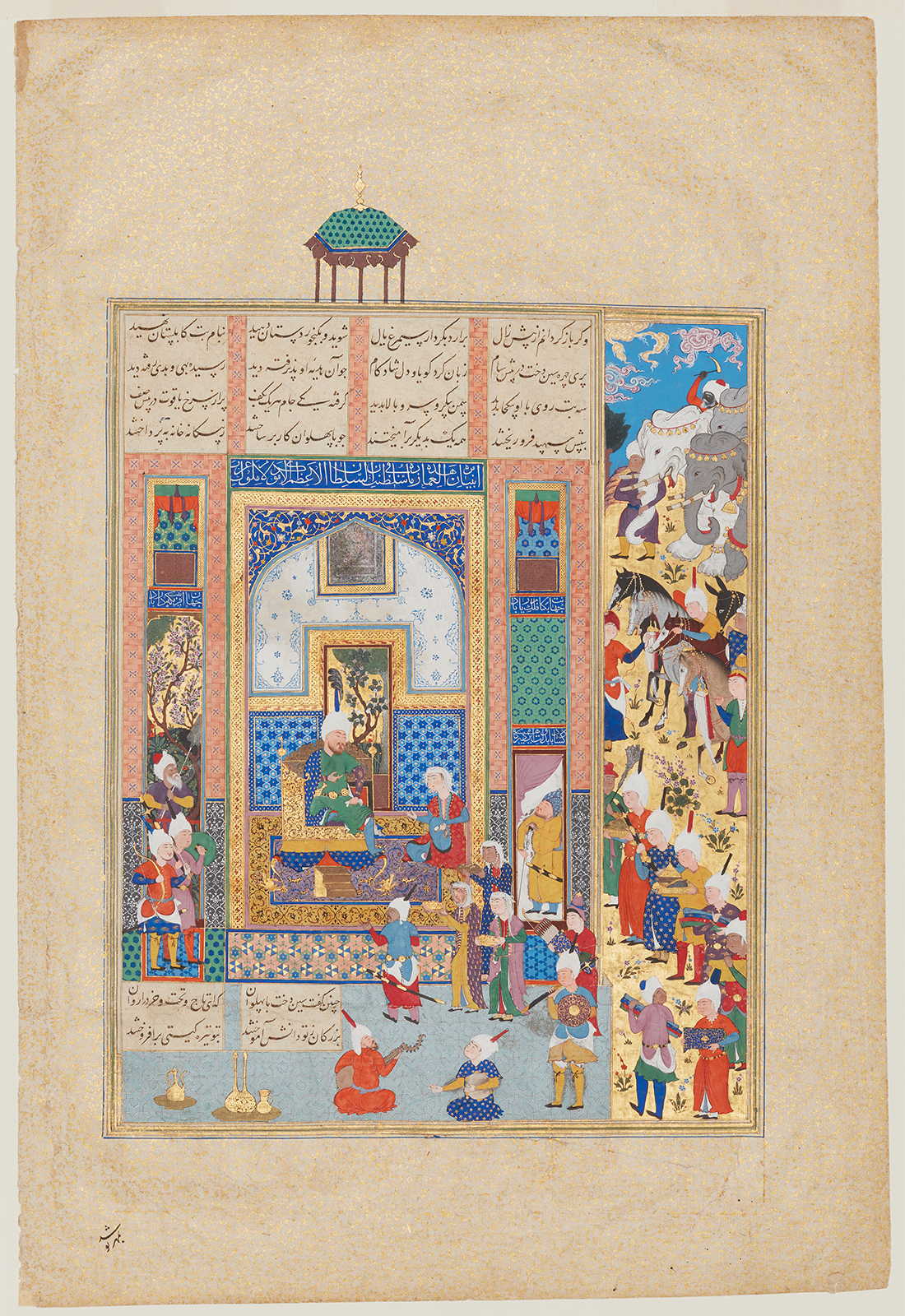

Sindukht comes to Sam Bearing Gifts

Folio from the Shahnameh (Book of Kings) of Shah Tahmasp

- Accession Number:AKM496

- Creator:Attributed to Qadimi of Gilan and ‘Abd al-Vahhab of Kashan

- Place:Iran, Tabriz

- Dimensions:46.5 x 31.2 cm

- Date:ca. 1525–1530

- Materials and Technique:Opaque watercolour, ink, and gold on paper

Firdausi’s epic poem the Shahnameh, completed in 1010, recounts the history of all of Iran’s shahs (kings) up to the Arab conquest in 642 AD and the country’s adoption of Islam. Five centuries later, it inspired the creation of the richly illustrated Shahnameh produced for Shah Tahmasp (r. 1524-76), the second shah of the Safavid dynasty. AKM496 (folio 84 verso) depicts an episode related to Shah Manuchihr, grandson of Iraj and descendant of Faridun (see AKM495). Manuchihr’s decision to order his leading paladin Sam to mount an Iranian attack on Kabul, ruled by King Mihrab, provides the context for this painting.

See AKM155 for an introduction to The Shahnameh (Book of Kings) of Shah Tahmasp

Further Reading

Manuchihr ordered the attack upon learning that Sam had allowed his son to marry Mihrab’s daughter Rudabeh, who, like her father, was a descendant of the evil king Zahhak. To avert this attack and prevent her own execution, Mihrab’s wife Sindukht gathered horses, elephants, silk, gold coins, slaves, and gems and travelled to Sam’s court in the guise of a diplomatic envoy. Not suspecting Sindukht’s true identity, Sam decided to accept the gifts to be held by Zal’s treasurer, thus not directly involving Manuchihr or Zal. With Sam’s agreement to her gifts, Sindukht’s companions came forth with bowls of rubies to pile before Sam. She then appealed to Sam to spare Kabul, and when asked to identify herself, she first asked for immunity from harm.

This painting is attributed to two artists, Qadimi of Gilan and ‘Abd al-Vahhab of Kashan,[1] who worked on the Shah Tahmasp Shahnameh under the direction of Sultan Muhammad, painter of the famed “Court of Kayumars” (AKM165). Unlike “Salm and Tur Receive the Reply of Faridun and Manuchihr” (AKM495) by ‘Abd al-‘Aziz, it does not bear elements of Sultan Muhammad’s own style. Instead, it uses forms and formal relationships that recall late 15th-century Turkmen painting from Gilan: human figures are doll-like, possessing large heads and squat bodies.[2] Moreover, the figures in this folio do not interact with one another, as they would if conceived by Sultan Muhammad; none whispers in his neighbour’s ear or even tips his head in another’s direction. The two musicians, one playing the ‘oud (lute) and the other holding a daf (a type of tambourine) in his left hand and castanets in his right, do not even meet each other’s gaze, though they seem to be playing together.

Despite its relative simplicity and conservative style, the painting does contain lively details, such as the ranks of attendants at the right with rolls of silks, golden platters, a precious casket, fully equipped horses, and a trio of elephants decorated with strings of bells. Inanimate objects such as the snarling dragons’ heads that serve as legs to the throne or animals such as the grey horse whinnying and raising its leg or the white elephant with its long, wiggly trunk provide the animation that is muted in the human figures in this painting. The frontal rendering of the grand pavilion reflects a simple and direct Turkmen style while evoking Safavid palaces with their tiled surfaces and majestic inscriptions.

The Shahnameh produced for Shah Tamasp is represented in the Aga Khan Museum Collection by ten paintings (AKM155, AKM156, AKM162, AKM163, AKM164, AKM165, AKM495, AKM496, AKM497, AKM903) out of a total of 258 illustrations in the original manuscript.

— Sheila R. Canby

Notes

[1] See Dickson and Welch, vol. 1, 201, where this painting is attributed to both painters on the basis of the figures’ round heads and a slightly provincial approach to the composition.

[2] Qadimi must have been versed in this painting style in Gilan before moving to Tabriz. The most famous illustrated manuscript from Gilan is the “Big-Head” Shahnameh, completed in 1494. See Robinson, 159–62.

References

Dickson, Martin B. and Stuart Cary Welch. The Houghton Shahnameh, 2 vols. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1981. ISBN: 9780674408548

Robinson, B.W. and Ernst J. Grube, G.M. Meredith-Owens, and R.W. Skelton, 159–62. Islamic Painting and the Arts of the Book. London: Faber, 1976. ISBN: 9780571108664

Note: This online resource is reviewed and updated on an ongoing basis. We are committed to improving this information and will revise and update knowledge about this object as it becomes available.