Click on the image to zoom

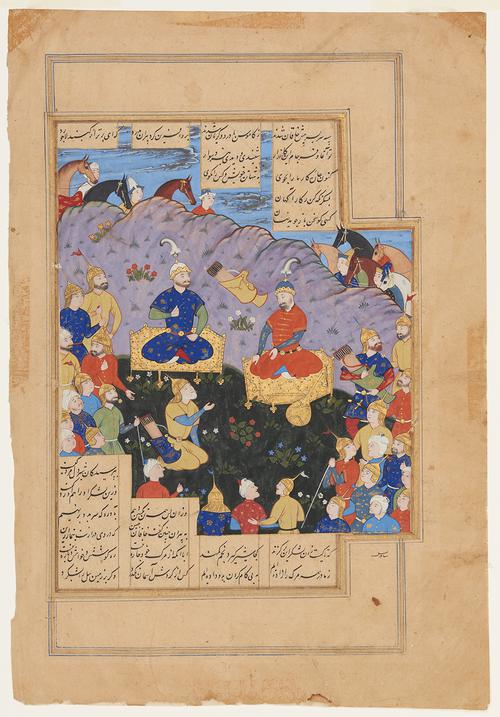

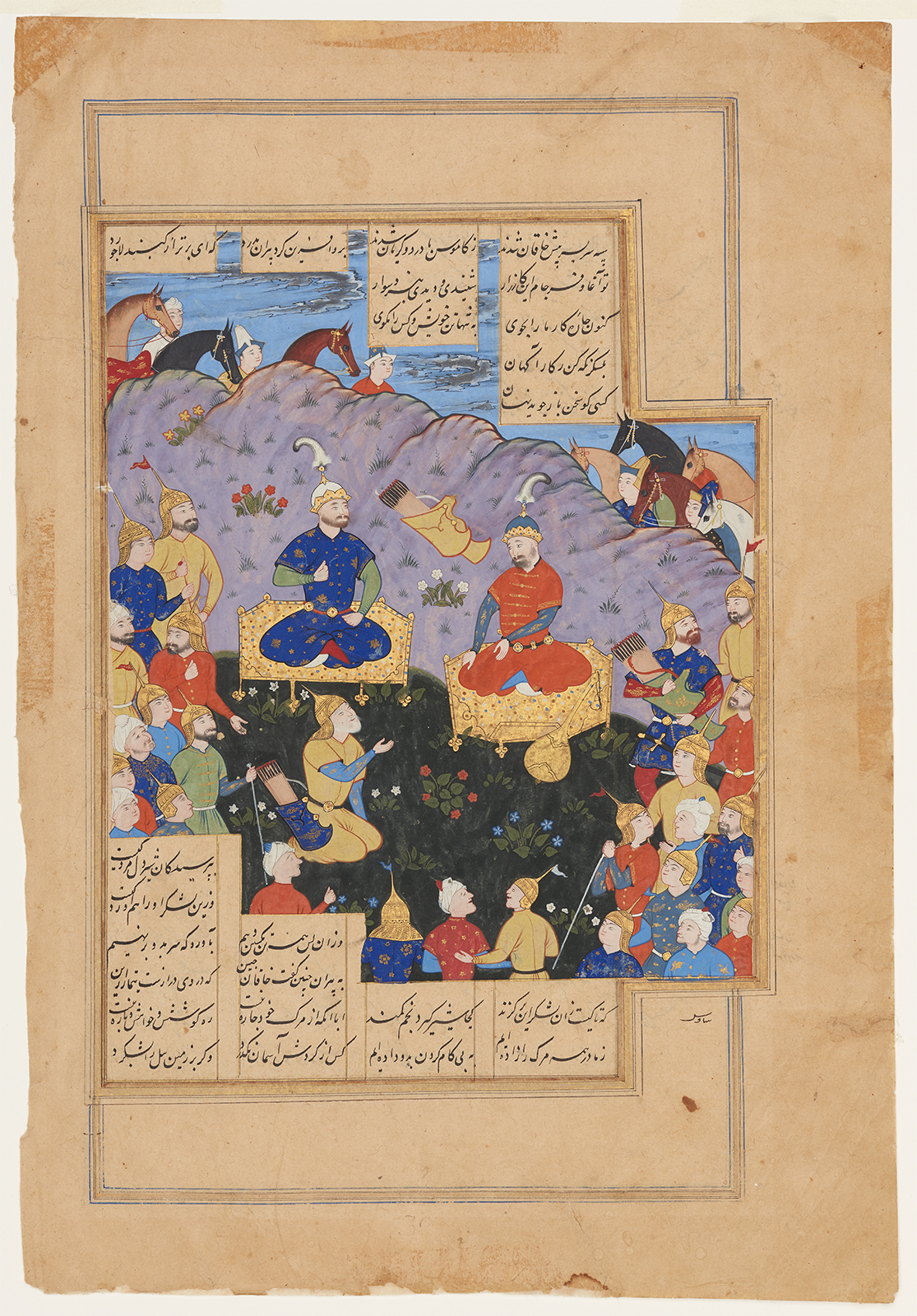

The Khaqan of Chin consults his advisors on the war with Iran

Folio from the Shahnameh (Book of Kings) of Shah Ismail II a

- Accession Number:AKM70

- Place:Iran, Qazvin

- Dimensions:45.5 x 31.2 cm

- Date:1576–77

- Materials and Technique:opaque watercolour, gold, silver and ink on paper

The miniature painting “The Khaqan of Chin consults his advisors on the war with Iran” is from a dispersed illustrated manuscript of the Shahnameh (Book of Kings), completed by the Persian poet Firdausi ca. 1010. Shah Ismail II (r. 1576–77) [1] commissioned the manuscript, following the examples of his grandfather, Ismail I, and father Shah Tahmasp, both of whom showed interest in Firdausi’s epic at one time during their reigns. Ismail II’s Shahnameh can be seen as a link in the chain of royal copies of the Book of Kings, after Shah Tahmasp’s spectacular manuscript and forming a bridge to the next period of royal patronage of the epic under Shah ‘Abbas (1587–1629). The manuscript was left unfinished upon Ismail II’s death. However, for a brief period, Ismail II’s atelier employed a number of artists who contributed to the illustration of the Shahnameh, including Siyavush, Sadiqi Beg, Naqdi, Murad Dailami and Mihrab. These artists did not sign their work, and attributions were probably made by the contemporary royal librarian. This painting is attributed to Siyavush, a Georgian slave at the court of Tahmasp who contributed an impressive total of 22 paintings to this manuscript. The scene shows the Khaqan and his advisors taking stock of the death of their champion Kamus-i Kashani in the recent battle with Rustam.

Further Reading

The title given for this painting is often “Piran consults with Kamus and the Khaqan of Chin.”[2] However, the illustration is located in the text at the point where the Khaqan and his court discuss the consequences of the death of Kamus and the prospects for continuing the war with Iran. The confusion in titles requires a fresh identification of the figures. One is the downcast Khaqan, dressed in red on the right-hand throne. Before him kneels the trusted greybeard advisor, Piran, who is encouraging him to find a new champion. It seems likely that the powerful, confident figure in blue on the other throne is Chingish, who is introduced like this: “A proud, Khusrau-worshipping knight arrived and struck his chest with his hand [in readiness] for this challenge.”[3] It is Chingish who next takes up the fight against Rustam.

The superior artistry of Siyavush is immediately evident here, not only in the individual characterization of the three key figures, but also in the way they interact with each other and with the text. Anthony Welch’s discussion of this painting, made when the artist was about 40, notes that here “we come to a full understanding of Siyavush’s work in the Shahnamah.”[4] Welch observes the range of characters delineated in the surrounding circle of courtiers who have all arrived to discuss the situation. The stepped format and its extension in the margin provide an interestingly structured space, enhanced by the way the sky is carried on into the columns between the verses above, while the distribution of the colours across the picture, especially the sky blue, red, and pale ochre, pull the whole composition together. The attribution to Siyavush is found in the angle of the inner frame on the bottom right (once masked by the original mounting). Although a second, outer margin is also ruled, awkwardly joining the inner frame, it is not needed either for the text or any exuberant expansion of the painting.

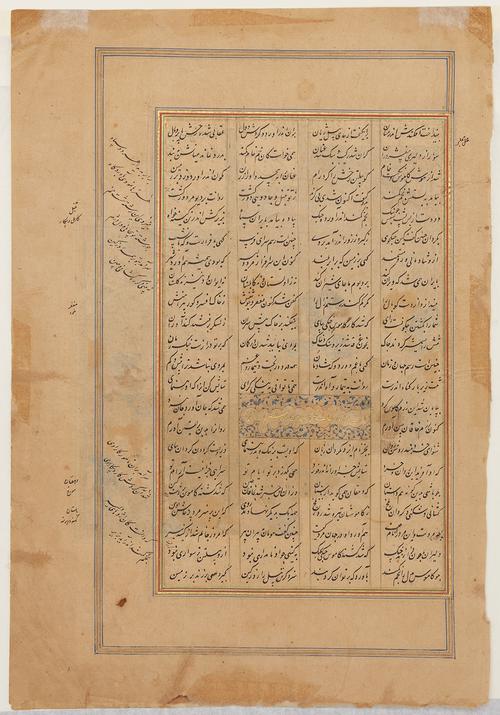

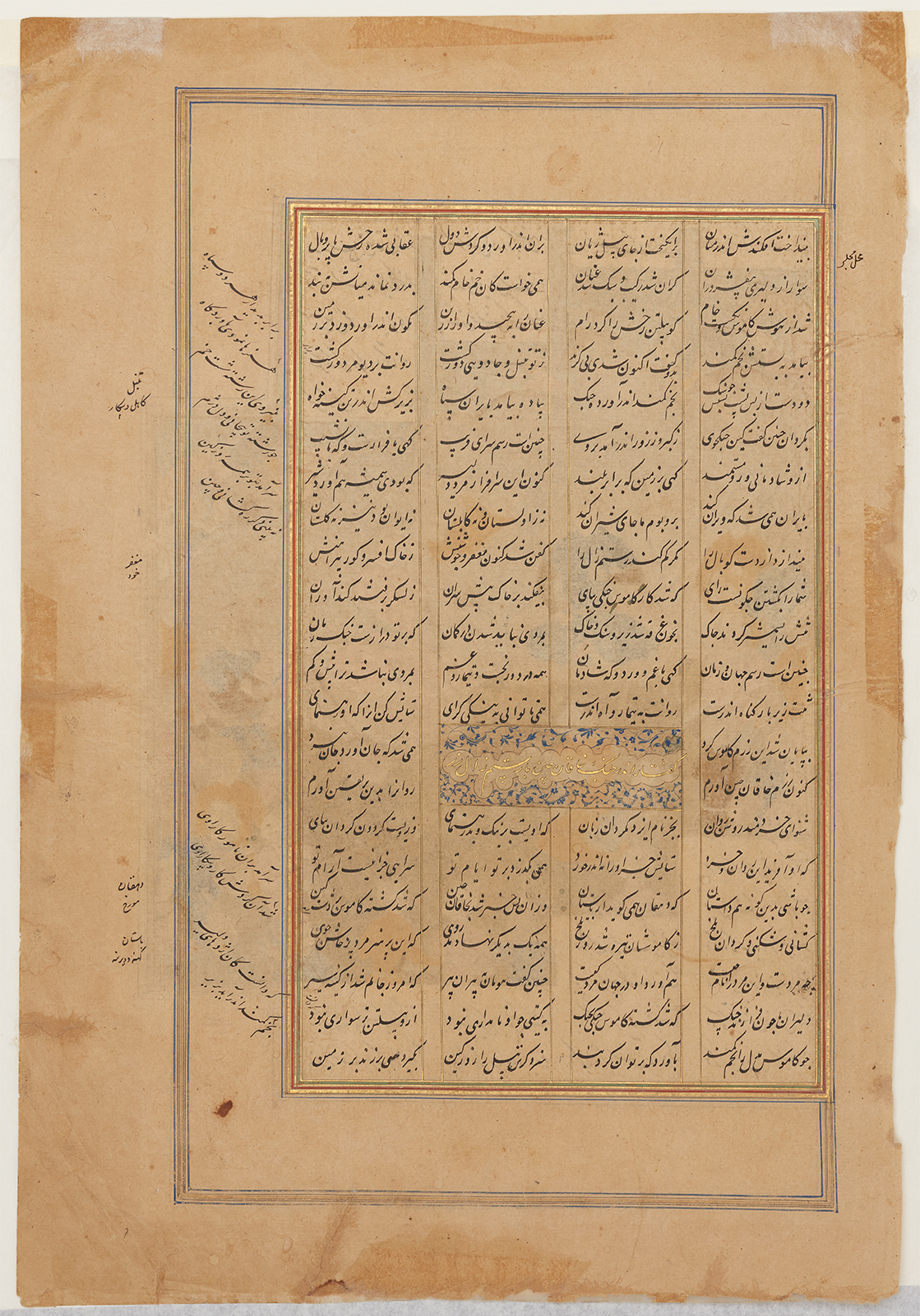

The recto side of this folio is a text page with an elegant rubric that reads: “Narrating the war of the Khaqan-i Chin with Rustam-i Zal-i Zar” in gold nasta‘liq script. Here, the outer ruled margin is used to accommodate some verses of the poem that were omitted by mistake. More interesting, perhaps, is the choice of words glossed in the outer margin on the left: tanbal (“lazy”), glossed as kahil, bi-kar (“slothful” or “not working”); and mighfar, glossed as khud (“helmet”). At the top of the right hand side, the words mahall-i majlis (“place for a picture”) suggest that an illustration was intended here. A likely candidate could be the death of Kamus, who was thrown from his horse by Rustam. Such a scene was a very popular subject for illustration.[5]

Shah Ismail II’s copy of the Shahnameh

Shah Ismail II was the third ruler of the Safavid dynasty in Iran. The founder of the dynasty, though not of the fortunes of the family, was his grandfather, Ismail I (r. 1501–24). He in turn was descended from the sufi Shaikh, Safi al-Din (“Pure of faith,” d. 1334), a Muslim mystic who established his religious order in the town of Ardabil in northwest Iran. Ismail I defeated the rival powers of the time—a Turcoman dynasty in western Iran and the Uzbeks in Khurasan and Transoxiana—and began the unification of the eastern and western provinces of the kingdom while enforcing Shiite sectarian Islam as the official religion of the Safavid realm. The dynasty governed Iran for over 200 years, perishing at the hands of an Afghan invasion in 1722.

Ismail I was succeeded by his young son, Shah Tahmasp (r. 1524–76), who moved the capital from Tabriz to Qazvin and consolidated the empire, both in terms of territory and in promoting the Shiite faith. Although Tahmasp’s long reign provided some stability, underlying tensions between competing military factions (the so-called Qizilbash, or “Red Head” forces) that marred the opening years of his reign resurfaced upon his death. His son, Ismail II, who had spent almost 20 years in prison accused of plotting against Tahmasp, was released by one faction of Qizilbash. This faction killed Ismail II’s younger half-brother Haidar and brought him to the capital in June 1576, where he was formally crowned in August. Possibly affected by years of isolation, possibly determined to distance himself from his father’s policies, or simply in an effort to secure his position, Ismail initiated a purge of his Safavid relatives and seems to have been interested in reviving the mainstream Sunni faith. His reign, marked by bloodshed and dispute, ended in November 1577 with his death in mysterious circumstances.

During the short period of his rule, 1576–77, Ismail II followed the example of his grandfather, Ismail I, in commissioning a copy of the Shahnameh, the great epic of the Persian kings from mythical times to the Arab invasions of the early 7th century that destroyed the Persian Empire and introduced the new Islamic religion. The Shahnameh was completed ca. 1010 by the poet Firdausi, and after a lapse of some two centuries and the creation of a new Persian Empire under the Mongols, the book became a symbol of Iranian kingship and the vehicle for asserting the legitimacy of a sequence of royal regimes.

Although Ismail I initiated the production of a regal copy of the Shahnameh, it was barely started on his death, and was famously completed in the 1530s under Shah Tahmasp, in a superb and lavishly illustrated copy that was presented by Tahmasp as a coronation gift to the Ottoman sultan Selim II in 1568. By this time, Tahmasp had lost interest in patronizing the arts, and it was his nephew and son-in-law, Ibrahim Mirza, governor of Khurasan, who maintained a princely atelier in Mashhad. Ismail II had Ibrahim killed in 1577, but revived the royal workshops neglected by Tahmasp in his later years, gathering a group of talented artists around him to produce a new copy of the Shahnameh. This is a clear sign of Ismail’s assertion of royal authority, a trend continued by his nephew, Shah ‘Abbas, who came to the throne in 1587, having escaped death due to Ismail’s demise before the order to kill him could be carried out. The intervening decade, of the rule of Muhammad Khudabandeh (r. 1577–87), who was partly blind, saw a renewed decline in royal patronage.

Ismail II’s Shahnameh, therefore, should be seen as a link in the chain of royal copies of the Book of Kings, after Shah Tahmasp’s spectacular manuscript and forming a bridge to the next period of royal patronage of the epic under ‘Abbas. Details of the copy are not well known, but the manuscript seems to have been left unfinished upon Ismail’s sudden death. It was last seen intact at an exhibition at the Musée des arts décoratifs in Paris in 1912, having apparently left the royal library in Tehran during the reign of Muhammad ‘Ali Shah Qajar (r. 1907–09). The unscrupulous Belgian art dealer Georges-Joseph Demotte (d. 1923) was quick to dismember the precious manuscript, often cutting down the pages in the process and sometimes adhering them onto a mount before selling them to a number of collectors, among whom was the Baron de Rothschild. Basil Robinson has identified 55 paintings from the Ismail II Shahnameh, nine of which are now in the Aga Khan Museum Collection.

Ismail II’s atelier employed a number of artists who contributed to the illustration of the Shahnameh, several of whom created miniatures in the Aga Khan Museum Collection, namely Siyavush, Sadiqi Beg, Naqdi, Murad Dailami and Mihrab. Although they did not sign their work, attributions were made in the margins of each picture, probably by the contemporary royal librarian. Siyavush was a Georgian, captured during a Safavid expedition in the Caucasus. He entered the service of Tahmasp, who encouraged his training as an artist. His known work is associated with the Ismail II Shahnameh, to which he was the chief contributor; he died before 1616. Sadiqi Beg (1533/34–1609) started his career as a Qizilbash warrior, but turned to art around 1565 and was attached to Tahmasp’s court in Qazvin. He and Siyavush both trained under Muzaffar ‘Ali (d. 1576) and were at the forefront of the new generation of artists collected by Ismail II. Sadiqi Beg went on to become head of the royal library (kitabdar) under Shah ‘Abbas. Of the other three painters who worked on Ismail’s Shahnameh, namely Naqdi, Murad Dailami and Mihrab, nothing is known beyond their work.

Although Ismail II’s Shahnameh cannot compare with the magnificence of Shah Tahmasp’s copy, it is a large and impressive manuscript, important in its historical context and as a witness to the various talents and styles of a number of artists identified by name who worked during the transitional period from the 16th to the 17th century and experienced the shift in focus from Qazvin to the new capital, Isfahan.

The Aga Khan Museum Collection has eight folios from the Shahnameh (Book of Kings) of Shah Ismail II, see AKM70, AKM71, AKM72, AKM99, AKM100, AKM101, AKM102, AKM103.

— Charles Melville

Notes

[1] Shah Ismail II was the third ruler of the Safavid dynasty (1501–1722). Reuniting the eastern and western provinces of Iran, the Safavids introduced Shiite Islam as the official state religion. Ismail II, son of Tahmasp (r. 1524–76), seems to have been inclined to return to Sunnism, but in this and his artistic patronage he was perhaps simply seeking to distance himself from his father’s regime. He was murdered after ruling for 18 months.

[2] See Welch, Artists for the Shah, 25, pl. 2; Robinson, “Isma‘il II’s Shahnama,” 4, no. 35; Canby, Princes, Poets and Paladins, 61, no. 36.

[3] Shahnameh, ed. Mohl, “Khaqan-i Chin,” verse 30; ed. Khaleghi-Motlagh, “Kamus-i Kashani,” verse 1502: eight verses after the text on this page.

[4] Welch, Artists for the Shah, 25–6.

[5] The page starts at Mohl, verse 1568; Khaleghi-Motlagh, verse 1453, at exactly this point.

References

Canby, Sheila R. Princes, Poets & Paladins. Islamic and Indian Paintings from the Collection of Prince and Princess Sadruddin Aga Khan. London: British Museum, 1998. ISBN: 9780714114835.

---. The Golden Age of Persian Art 1501-1722. London: British Museum, 1999. ISBN: 9780714124049.

Falk, Toby, ed. Trésors de l’Islam. London: Philip Wilson, 1985. ISBN: 9780856671999.

Gandjei, TO. “Notes on the Life and Work of Sadiqi: A Poet and Painter of Safavid Times,” Der Islam 52, no. 1 (1975), 112–18.

Khaleghi-Motlagh, Djalal, ed. Shahnameh. Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers in association with Bibliotheca Persica, 1992.

Marteau, G. and H. Vever. Miniatures persanes: tirées des collections de MM. Henry d’Allemagne, Claude Anet, [e. a] / et exposées au Musée des arts décoratifs, juin–octobre 1912. Paris: Bibliothèque d’art et d’archéologie, 1913.

Melikian-Chirvani, Assadullah Souren. Le chant du monde. L’Art de l’Iran safavide 1501–1736 Paris: Musée du Louvre, 2007. ISBN: 9782757201268.

Meyer, Joachim and Peter Wandel. Shahnama. The Colourful Epic about Iran’s Past. Copenhagen: David Collection, 2016. ISBN: 9788788464153.

Mohl, Jules, ed. Shahnameh (Livre des rois). Paris: Impr. Nationale, 1876–78.

Newman, Andrew J. Safavid Iran. Rebirth of a Persian Empire. London: I.B. Tauris, 2007. ISBN: 9781845118303.

Rajabi, Muhammad ‘Ali, ed. Masterpieces of Persian Painting. Tehran: Museum of Contemporary Art, 2005. iSBN: 9789649677002.

Robinson, BW. Persian and Mughal Art. London: Colnaghi, 1976.

---. “Isma‘il II’s copy of the Shahnama,” Iran 14 (1976), 1–8; reprinted in B.W. Robinson, Studies in Persian Art, Vol. II. London: Pindar Press, 1993, 290–305. ISBN: 9780907132431.

---. “Shah Ismā‘īl II’s copy of the Shāh-nāma: Additional material,” Iran 43 (2005), 291-99. DOI: 10.1080/05786967.2005.11834675

Welch, Anthony. Collection of Islamic Art: Prince Sadruddin Aga Khan, Vols. I and 3. Geneva: Chateau Bellerive, 1972/1978.

---. Artists for the Shah. Late Sixteenth-Century Painting at the Imperial Court of Iran. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1976. ISBN: 9780300019155.

---. “Painting and Patronage under Shah ‘Abbās,” Iranian Studies 7, nos. 3–4 (1976), 458- 508.

--- and Stuart Cary Welch, Arts of the Islamic Book – the Collection of Prince Sadruddin Aga Khan. Ithaca & London: Cornell University Press, 1982. ISBN: 9780801415487.

Note: This online resource is reviewed and updated on an ongoing basis. We are committed to improving this information and will revise and update knowledge about this object as it becomes available.