Click on the image to zoom

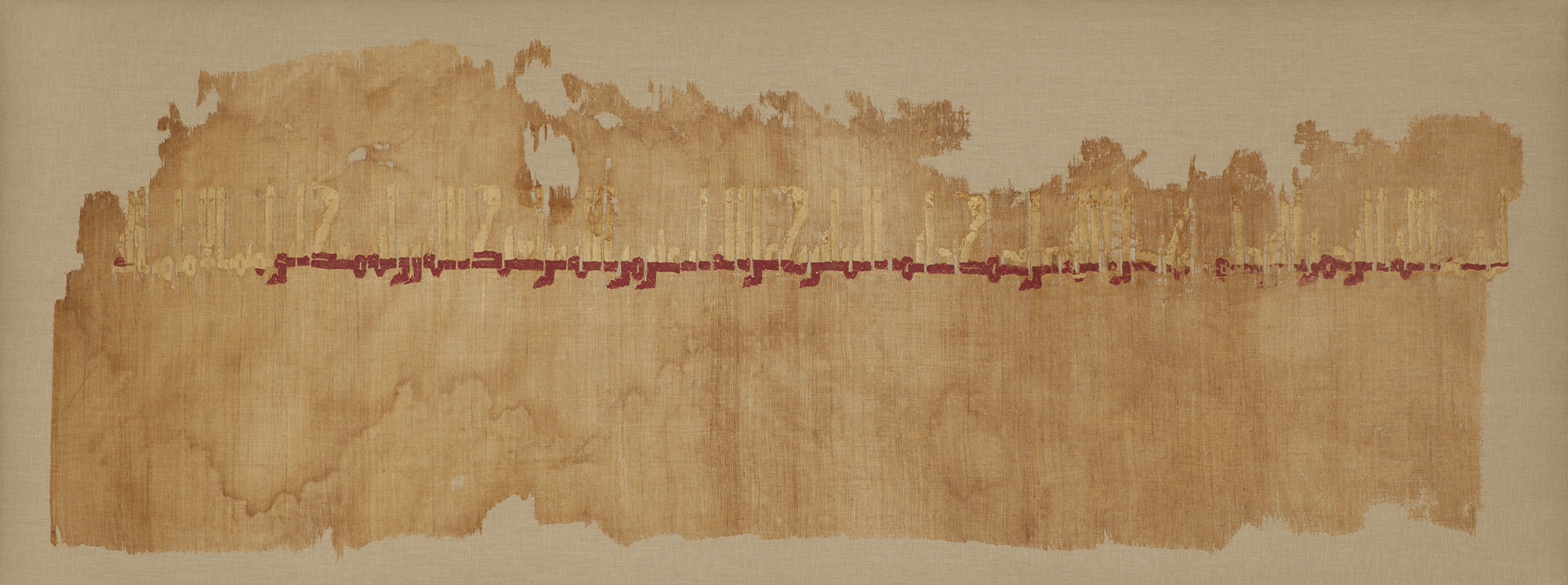

Tiraz textile with red inscription

- Accession Number:AKM670

- Place:Egypt

- Dimensions:151 x 51 cm

- Date:third quarter of 10th c.

- Materials and Technique:Linen tabby; with red silk tapestry-woven inscription

The term “tiraz” means “embroidery” in Persian, but, over time, it has come to identify an inscription band found on all manner of objects—from textiles to metalwork to architecture. The inscription on this 10th-century textile names the first Fatimid ruler, Fatimid Caliph al-Mu’izz (925-975), who is most remembered for moving the Fatimid capital from Tunisia to Egypt and, in 969, for founding the city of Cairo. The inscription ends with an illegible word and a blank space, the meaning of which is unclear. In contrast to the textile, which has a plain weave, the inscription has been tapestry woven, using coloured silk threads wrapped around the warps to form the design. This textile was likely discovered in the burial grounds of Cairo, where most of the surviving examples of early Islamic costumes and furnishings have been found.

Further Reading

A recent study of the manner in which the tiraz textiles occur in burials observed that the inscription bands were laid across the head. As these inscriptions generally include benedictions on the Caliph, his family, and the Prophet, or simply generic blessings, these words “spoke” for the deceased. The tiraz textile literally placed the prayers in the mouth of the deceased.

Both the inscription and the finished edge (“selvage”) along the left side of this 10th-century textile are well-preserved. The inscription reads “In the name of God, the Beneficent, the Merciful; may God’s blessings be upon Muhammad, Seal of the Prophets and upon [all?] his family [victory?] from God to the Servant of God and his viceroy, Maʻadd Abi Tamim, the Imam…?”

However, the upper portions of the letters have lost their red dye, creating a two-tone effect which may indicate the use of different dye-lots. The weaver would have laid in the wefts corresponding to the bottom of the letters first. Perhaps he ran out of the higher-grade red silk when he arrived at the upper level of the letters and substituted something else to complete the weaving. The style of the Kufic script is monumental, similar to that found on tiraz textiles made earlier in Egypt for the Abbasid rulers.

Tiraz textiles were produced in “public” or “private” factories, which were funded, as their names suggest, either by public or royal funds. Royal textile factories existed in many towns in Egypt and throughout the eastern Abbasid empire. The textiles bear inscriptions naming the Caliph, the date, and the place of manufacture. Some also provide the name of the official facilitating the order, often the wazir.

— Lisa Golombek

Note: This online resource is reviewed and updated on an ongoing basis. We are committed to improving this information and will revise and update knowledge about this object as it becomes available.