Click on the image to zoom

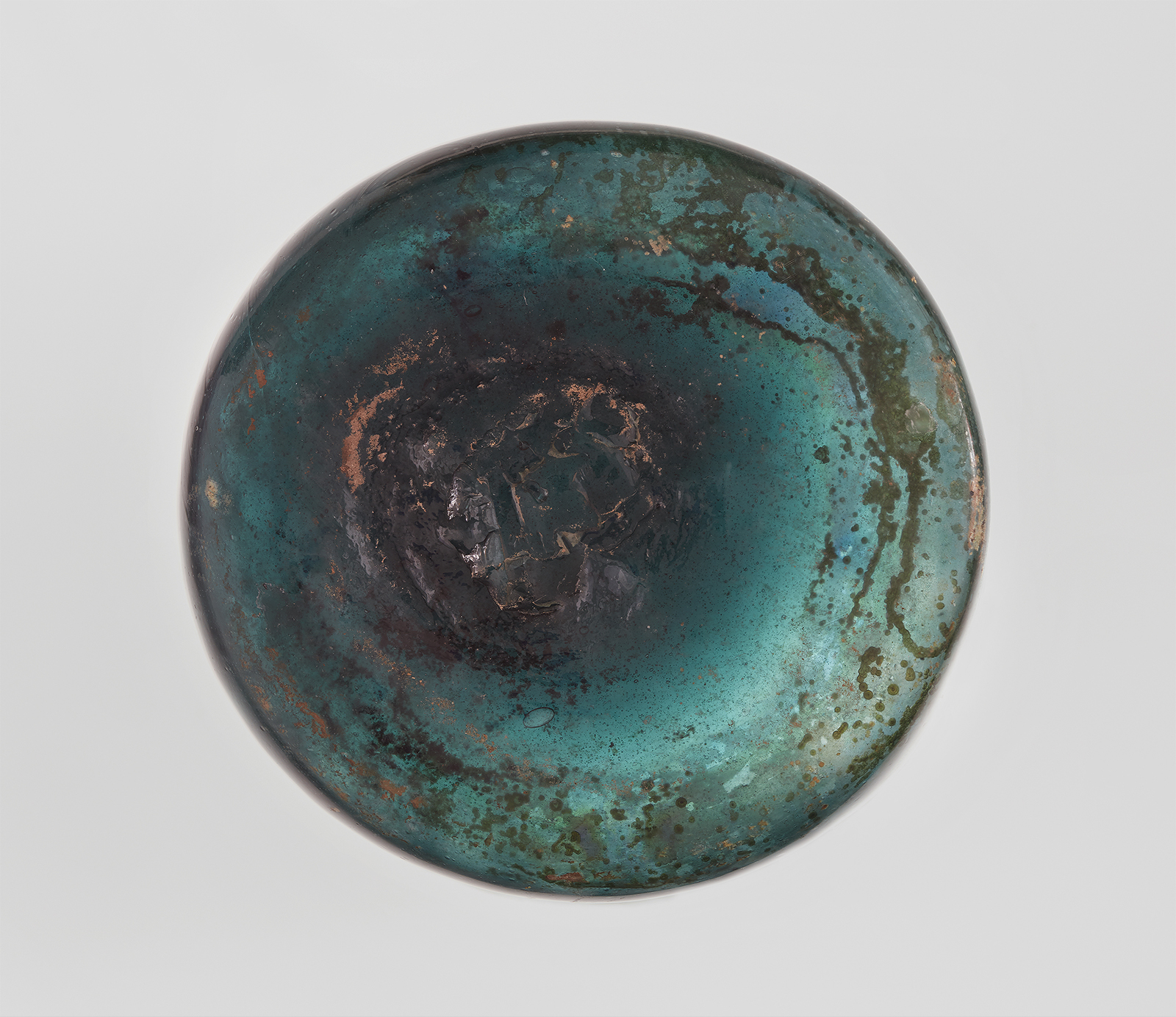

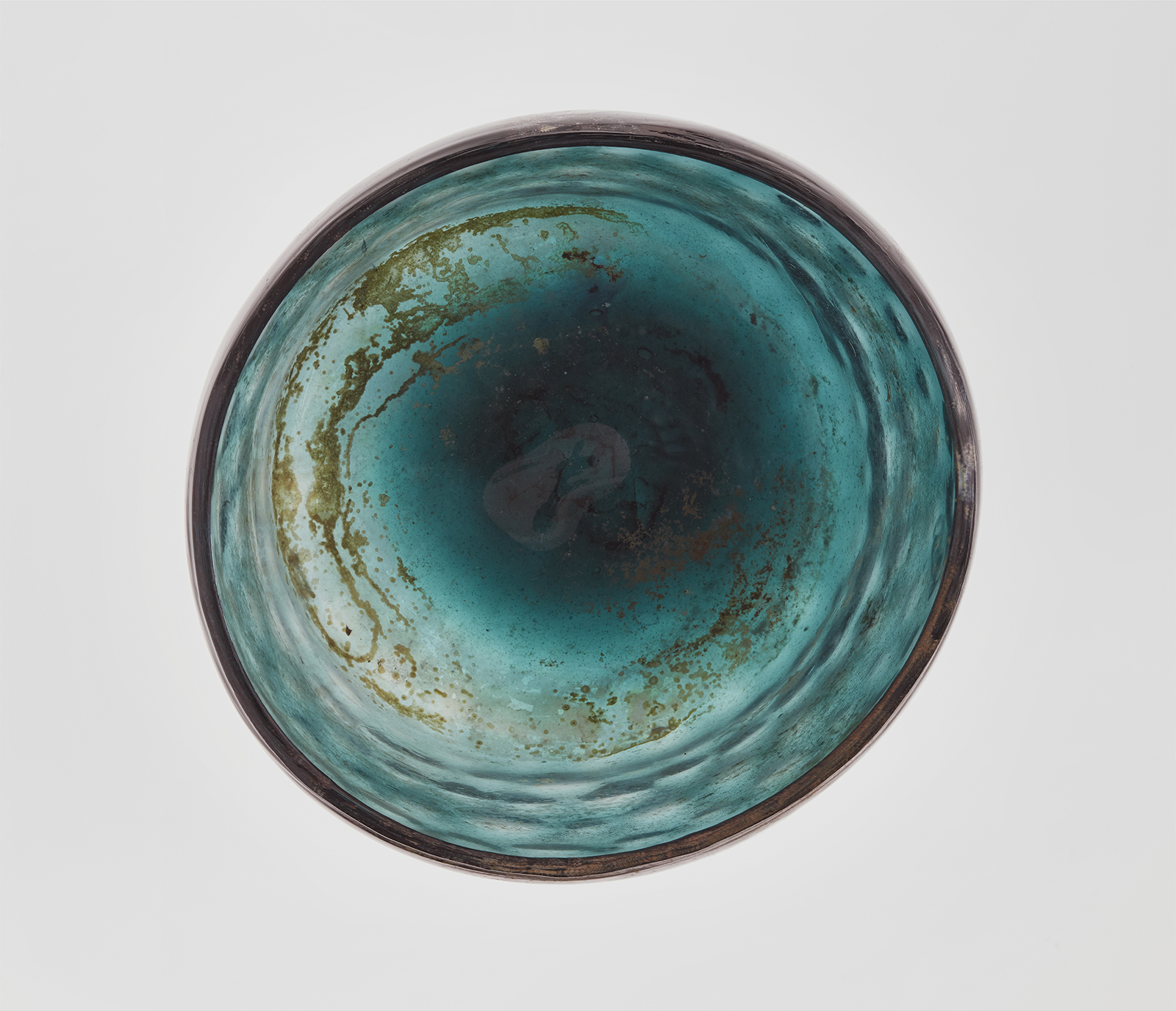

Beaker

- Accession Number:AKM656

- Place:Egypt or Syria or Iran

- Dimensions:12.1 cm x 14 cm

- Date:11th–13th century

- Materials and Technique:glass, transparent blue, patches of iridescence; mould blown, tooled, worked on the pontil

The pattern on this cylindrical beaker of slightly irregular form with bulging sides consists of rows of lozenges arranged in a honeycomb pattern, one of the most popular decorative patterns used since late antiquity.[1] The rather unusual blue colour of this beaker points towards an Iranian origin, possibly as late as the 11th to 13th centuries. It may be contemporary with long-necked, mould-blown bottles sharing the same or similar patterns (see AKM658).

Further Reading

More bottles than beakers seem to have survived, but this phenomenon may be accidental. Cylindrical beakers with the same height as diameter may have been used for many different purposes. The most typical use may have been as drinking glasses, because pincer-decorated inscriptions on some of them offer good wishes. They may even have been used as lamps, though the blue colour of this example was probably too dark for that use.

Most vessels with honeycomb patterns were produced by blowing the glass into a mould, possibly made of metal. The honeycomb decoration usually covered the base and wall, but the part near the rim was often plain. On this example the decoration ends under the rim. Results of such patterning could be very different depending on the thickness of the glass, the shape of the mould, and/or how much the vessel was blown further after having been removed from the mould. If taken out of the mould, a pontil (a hot metal rod with some glass attached to it) was pressed to the bottom of the bowl. On this beaker it resulted in a pushed-up bottom of irregular shape and a kick as well as a number of small impressions from working the warm metal on an uneven ground. The procedure occurred quickly and was necessary to manipulate the cylindrical shape of the beaker and to adjust it towards a smooth rim needed for a drinking glass.

Astonishingly, only a fragmentary beaker of an earlier period, probably of the 9th to 10th centuries, was found during the excavations in Nishapur in northeastern Iran. On this example, a honeycomb pattern began at the base with ovals, which turned into lozenges, ending 1.5 cm below the rim.[2] A beaker of considerable thickness in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York has a high cylindrical shape without bulging sides and thus a very different look. The hexagons of the honeycomb pattern also end well below the rim.[3]

Besides beakers, bowls[4] and different kinds of bottles were blown with the honeycomb pattern. A plate of the Fatimid period in the Museum of Islamic Art in Berlin[5] can be linked to the numerous vessels discovered on a ship which sank in Serçe Limanı near Bodrum on the Aegean coast around 1025 and had a cargo picked up on the Levantine coast. Cylindrical bowls were also found among the cargo.[6]

Most of the glass vessels mentioned must have been made for daily needs within Islamic households. It is impossible to suggest further detail regarding use, let alone details about the individual costs of such glasses. It is also not well known which parts of the society could actually afford such glasses. What we know from sources is the surprising fact that, during peaceful and prosperous periods, goods were transported over great distances. We also know from the objects themselves that even vessels for daily use could be decorated with patterns to please the customer.

— Jens Kröger

Notes

[1] David Whitehouse 2001, 113, no. 607 (beaker with flat base, 4.–6.th c.), 114, no. 609 (vessel with conical base, 4th c.).

[2] Kröger, 90–91, no. 123.

[3] Jenkins, 16–17, no.13.

[4] Whitehouse 2014, 96, no. 771 (12th –13th century)

[5] Kühn, 104–105, no.22.

[6] Bass, 115–121 (CB 43).

References

Bass, George F. et al. Serçe Limanı, Volume II: The Glass of an Eleventh-Century Shipwreck, College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2009. ISBN: 9781603443654

Jenkins, Marilyn D., “Islamic Glass. A Brief History." The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 54, no. 2 (1986).

Kröger, Jens. Nishapur. Glass of the Early Islamic Period. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1995. ISBN: 9780300192827

Kühn, Miriam with contributions by Andrea Becker and Jens Kröger. Vorsicht Glas! Zerbrechliche Kunst 700–2010. Berlin: Museum für Islamische Kunst - Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, 2010. ISBN: 9783938832691

Whitehouse, David. Roman Glass in The Corning Museum of Glass, Vol. II, Corning, NY: The Corning Museum of Glass, 2001. ISBN:9780872901506

---. Islamic Glass in The Corning Museum of Glass, Vol. II, Corning, NY: The Corning Museum of Glass, 2014. ISBN: 9780872901995

Note: This online resource is reviewed and updated on an ongoing basis. We are committed to improving this information and will revise and update knowledge about this object as it becomes available.