Click on the image to zoom

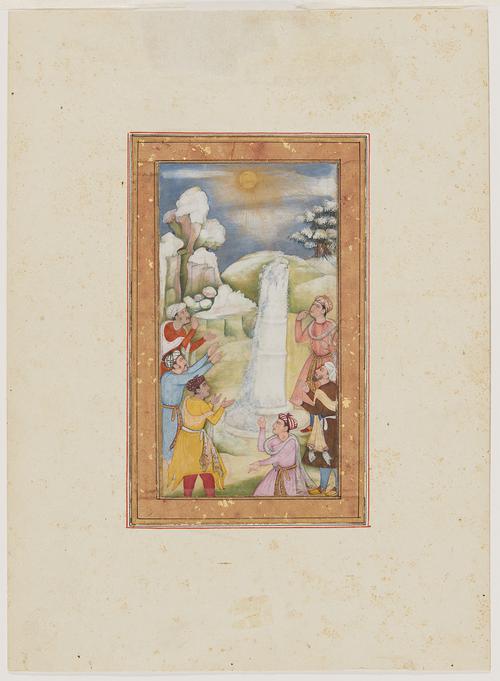

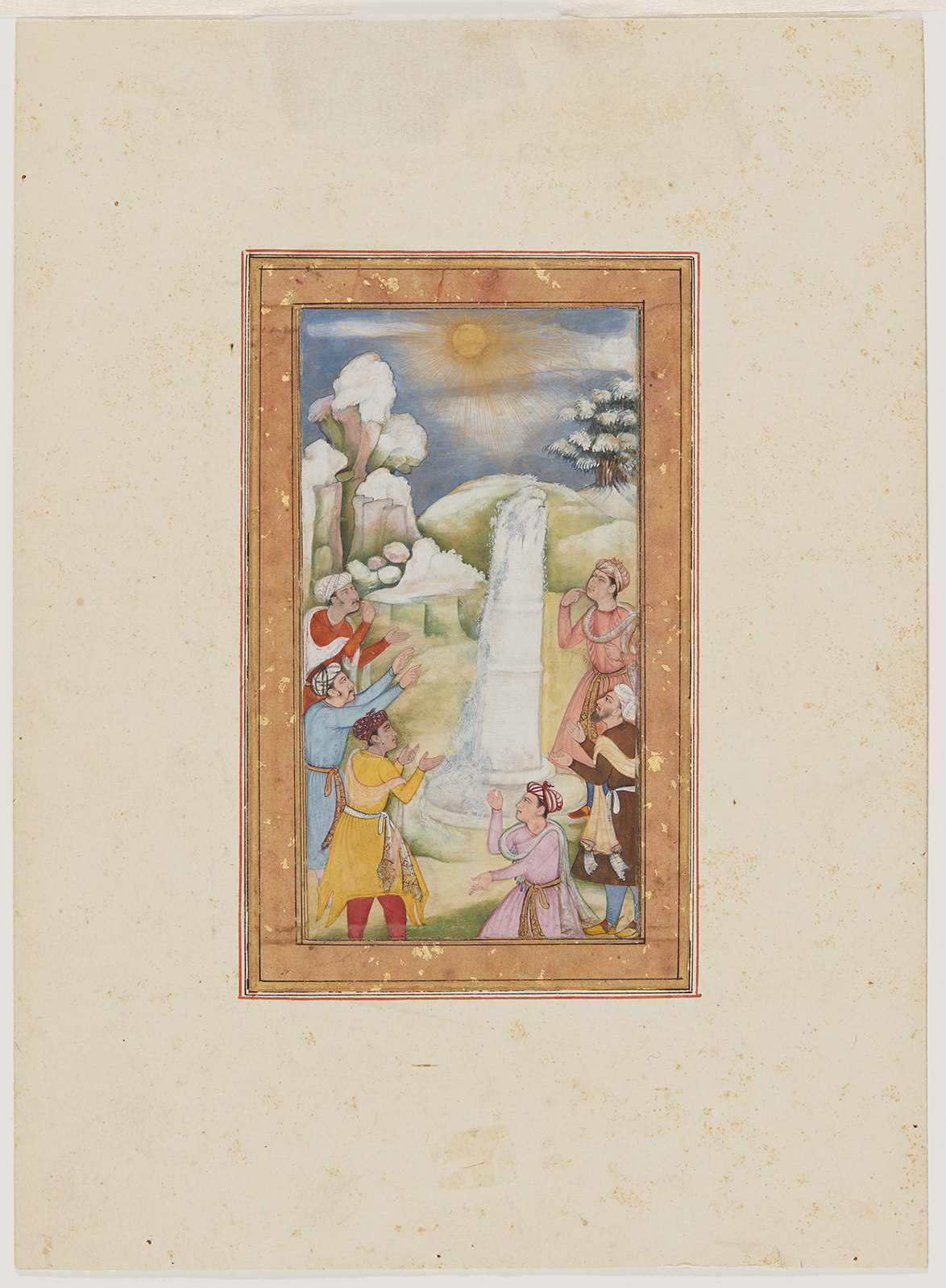

Mughal men admiring the miraculous ice lingam at Amarnath

- Accession Number:AKM154

- Place:India, Agra

- Dimensions:27.6 x 20.1 cm

- Date:ca. 1600

- Materials and Technique:opaque watercolour and gold on paper

Probably intended for an album made for royalty or nobility of Mughal India (1526–1858), this small painting represents a visit to the Amarnath cave, a Hindu shrine located in the Himalayan mountains in Kashmir. Wearing turbans and knee-high coats, three men stand around a natural ice lingham (stalagmite) that the artist has placed outside the cave in an act of artistic license. Some of the men stretch their arms, pointing at the lingam, while others stand with their palms open in supplication. The two men on the upper right and left of the stalagmite place their fingers to their mouth, in a gesture of awe and wonderment. According to Abu’l Fazl (1551–1602), court historian to famous Mughal emperor Akbar (r. 1556–1605), the cave was an ancient Hindu site that attracted many pilgrims who would come to worship the lingam. These pilgrims recognized the ice stalagmite as the image of Mahadeva, the great god Shiva, and believed that the lingham had the power to answer their prayers. The site is still active today as a pilgrimage destination for both Muslims and Hindus.

FURTHER READING

In his description of the Amarnath cave, Abu’l Fazl remarks that the lingam changes according to the seasons and the moon: “When the new moon rises from her throne of rays, a bubble as it were of ice is formed in the cave which daily increases little by little for fifteen days till it is somewhat higher than two yards, of the measure of the yard determined by His Majesty; with the waning moon, the image likewise begins to decrease, till no trace of it remains when the moon disappears.” [1] In the painting, the radiating sun, the snow-covered mountains, and the melting ice water on the column may allude to the summer season in Kashmir, when the Amarnath yatra (religious festival or procession) occurs.

The Mughals, a Sunni Muslim dynasty that came from Central Asia to North India in the early 16th century, supported political tolerance to the multiple ethnicities and religions within their empire. For reasons of religion, expediency and intellectualism, Emperor Akbar initiated a policy of sulh-i kull (“peace with all”) that made coexistence within India feasible. Both emperors Akbar and Jahangir were interested in other spiritual practices, especially of yogis and ascetics. After Akbar annexed Kashmir in 1586, he visited some of the holy men living in caves in the area. His son and successor, Jahangir, continued to cultivate relationships with yogis and dervishes alike. Although there is no historical record that Akbar or Jahangir visited this cave, they seem to have known about it and the yatra practice.

The Mughals believed that supporting mendicants, ascetics and holy men maintained the equilibrium of society and the world. These ideas were directly linked to Akbar’s and Jahangir’s policy of sulh-i kull and the administration of justice by preserving balance among diverse ethnic and religious groups. This painting can be viewed as a visual affirmation of Mughal ideology, openess and curiosity toward India’s diversity.

— Mika Natif

Notes

[1] Abu’l Fazl, The Ain-i Akbari of Abū al-Faz̤l ibn Mubārak, 3 vols. Trans. Henry Blochmann and H.S. Jarrett (1867–77; repr., Calcutta: Asiatic Society of Bengal, 2010), 2: 359–60.

References

The Ain-i Akbari of Abū al-Faz̤l ibn Mubārak. 3 vols. Trans. Henry Blochmann and H.S. Jarrett. 1867–77; repr., Calcutta: Asiatic Society of Bengal, 2010.

Diamond, Debra, ed. Yoga: The Art of Transformation. Washington, DC: Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, 2013. ISBN: 9781588344595

Ernst, Carl W. “Muslim Studies of Hinduism? A Reconsideration of Arabic and Persian Translations from Indian Languages.” Iranian Studies 36, no. 2 (2003): 173–195.

Kinra, Rajeev. “Handling Diversity with Absolute Civility: The Global Historical Legacy of Mughal Sulh-i Kull.” The Medieval History Journal 16, no. 2 (2013): 251–95.

Sharma, Sunil. “Safavid and Mughal Imperial Self-Representation in Two Album Pages,” in Harmony: The Norma Jean Calderwood Collection of Islamic Art, ed. Mary McWilliams. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Art Museums, 2013, 146–55. ISBN: 9780300176414

Wright, Elaine, Muraqqa’ Imperial Mughal Albums from the Chester Beatty Library, Dublin Alexandria, Va.: Art Services International; Hanover: Distributed by University Press of New England, 2008. ISBN: 9780883971543

Note: This online resource is reviewed and updated on an ongoing basis. We are committed to improving this information and will revise and update knowledge about this object as it becomes available.