Click on the image to zoom

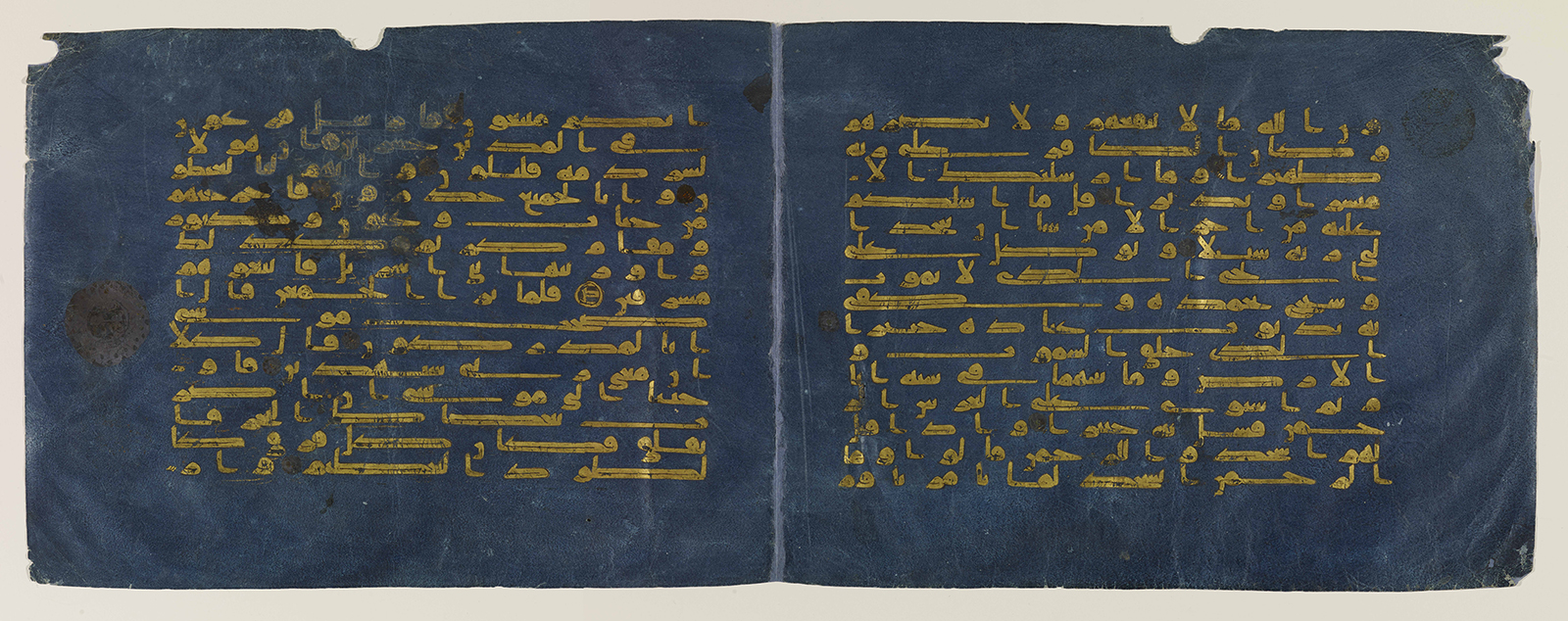

Two folios, from a manuscript known as the “Blue Qur’an”

- Accession Number:AKM477

- Place:Kairouan, Tunisia

- Dimensions: 30.9 cm × 81 cm

- Date:ca. 950

- Materials and Technique:Parchment coloured blue with indigo, gold, and silver leaf outlined in ink

The "Blue Qur’an" is one of the most distinctive manuscripts of the Qur’an. Its name derives from its striking appearance: fifteen lines of angular gold calligraphy written on dark blue parchment. Known to scholars since the beginning of the 20th century, it has an uncertain origin. Pages from this manuscript have been variously attributed to Iran, Iraq, Tunisia, Sicily, and Spain in either the 9th or 10th centuries. As the largest portion of the manuscript remains in Tunisia, where its presence was recorded some 700 years ago, it seems most likely to have been produced there during the 10th century. Its date of production was likely before 970, when the Fatimid caliphs moved their capital to Cairo, Egypt.

The original manuscript—originally kept in a special aloeswood box—once comprised seven bound volumes of about 90 parchment pages each. Each page was coloured with indigo and then laboriously written in gold leaf and embellished with silver markers (which have now tarnished to black). The laborious production of this manuscript involved slaughtering at least three hundred sheep to make the parchment, colouring the pages, writing the text, applying the gold leaf, and then outlining every letter of every word. Only a wealthy ruler could have ordered such a major artistic effort. The Qur’an was most certainly produced for a special occasion.

This bifolio (two-page spread) contains verses from chapters 25 and 26 (Surat al-Furqan and Surat al-Shu’ara), which would have been in the fourth of the seven original volumes. The two pages do not contain contiguous text, however: the right-hand page ends near the end of Q25:60; the left begins in the middle of Q25:53. This gap represents about 70 verses, indicating that at least one and probably two bifolios were originally placed between them. As on all the folios, silver disks mark the end of each verse. The gold circular marker on the eighth line of the left-hand page is the letter ṣād. This numeral indicates the end of verse 60, according to the abjad, or alphanumeric, system used for counting at that time. The large silver marker in the margin points to the gold marker in the text.

Some of the pages from Surat al-Baqara, the second chapter of the Qur’an, in the first volume of this manuscript were once in the collection of the Swedish diplomat and collector F. R. Martin (1868–1933). [1] Those pages might have been taken as tribute to the Ottoman capital from Tunisia in the 16th or 17th century. Other volumes apparently remained in Qayrawan, the religious capital of Tunisia, before many were taken to Tunis in the 20th century and dispersed to museums and private collections around the world.

Writing in gold, or chrysography, is particularly difficult and time-consuming. While it is possible to make gold ink by grinding gold leaf into a powder using honey or gum arabic, writing with gold ink uses much more gold than gold leaf, which gives a better effect using much less of the precious metal. The calligrapher wrote the text using a transparent adhesive, either egg white or gum arabic, and then covered the writing with incredibly thin gold leaf, which stuck only to the adhesive. The excess gold was brushed away (and collected for reuse) and the letters burnished to make them shine. The irregular edges of the letters were then refined with ink outlines, and the end of each verse was punctuated with a roundel in silver leaf. Groups of ten verses were marked in gold, with additional silver markers in the margins.

The beautiful combination of gold writing on deep blue pages has generated much speculation about its possible significance and meaning. Some scholars have suggested it symbolizes the mystical triumph of [God’s] light [that is, the Qur’an] over darkness, while others have seen it as merely a luxury item. The combination of gold and deep blue is found naturally in the rare lapis lazuli mined in Afghanistan, and it was appreciated from time immemorial, being used in the luxury arts of ancient Mesopotamia, Egypt, Greece, Rome, Byzantium, and the lands of Islam, as well as in China and Japan, in such media as jewellery, mosaics, textiles, and manuscripts. It is possible that the production of this manuscript was inspired by the Byzantine emperor’s gift to the Fatimid ruler of an imperial manuscript written in gold and silver on coloured parchment. It is unlikely, however, that it had much religious significance (apart from the text itself), for many scholars disapproved of copying the Qur’an in gold, and the colour blue (azraq) is mentioned only once in the Qur’an—and even then in a negative way. Contemporaries might have understood the colour to be "dark" or "sky-coloured." Whatever their original meaning, these pages from a beautiful manuscript continue to speak powerfully to us across the centuries.

- Jonathan M. Bloom

Notes

1. All the other pages in Martin’s collection derived from this same chapter. Martin claimed that he had acquired the pages in Constantinople (now Istanbul).

References

Bloom, Jonathan M. "The Blue Koran Revisited." Journal of Islamic Manuscripts 6 (2015): 196–218. DOI:10.1163/1878464X-00602005

George, Alain. "Calligraphy, Colour and Light in the Blue Qur’an." Journal of Qur’anic Studies 11 (2009): 75–125. DOI:10.3366/E146535910900059X

Note: This online resource is reviewed and updated on an ongoing basis. We are committed to improving this information and will revise and update knowledge about this object as it becomes available.