Click on the image to zoom

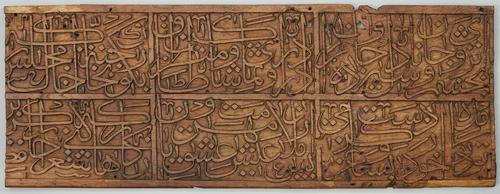

Wooden Panel with Verses by Hafiz

- Accession Number:AKM635

- Place:Iran

- Dimensions:52 x 138 cm

- Date:15th century

- Materials and Technique:carved plane tree wood

This large wooden panel inscribed with Persian poetry was most probably made during the Timurid period (ca. 1370–1507) in Iran.[1] It features six verses of a ghazal, or lyrical poem, written by the Persian poet Hafiz (1325–90).[2] Intricately carved, large-scale wooden panels such as this one would have served as wall fixtures, forming a calligraphic frieze that may have hung around a room. The text on this panel, which occupies its full surface, is written in the cursive thuluth script often used for monumental inscriptions. The panel is truncated on the left, indicating that the text would have continued on an adjoining fragment.

Further Reading

The verses read:

[First register:]

I confided heart and soul in the eyes and eyebrows of my beloved

Come, come and contemplate the arch and the window!

Say to the guardian of paradise: the dust of this meeting place [...]

[Second register:]

[...] do not falter in your task, pour the wine into the glasses!

Beyond your hedonism, your love for moon-faced beings,

Amongst the tasks that you accomplish recite the poem of Hafiz![3]

This poem describes a nighttime meeting between the poet and his beloved under the light of the moon.[4] The text’s themes—wine drinking, reciting poetry, and romantic encounters—suggest that the panels were originally affixed to walls in a secular setting, such as a reception room dedicated to receiving guests, eating, and drinking while listening to poetry.[5]

Poetry by Hafiz was widely read in 15th-century Iran. His works, such as the Diwan, were largely composed around the subjects of love and wine-drinking. The various references to the moon in the excerpt above fit squarely within these themes, as the moon was considered to be a paradigm of beauty in Persian literature.[6]

The reference to the eyes (chashm) and eyebrows (abru) of Hafiz’s beloved in the first verse recall the full and crescent moon respectively. The second to last verse, included in the central panel in the lower register, makes mention of moon-faced beings, or mahruyan. This term was frequently used in Persian poetry as a metaphor for utmost physical grace and allure.

While this wooden panel may have been placed in a secular, perhaps courtly setting, the technique of calligraphic wood carving in thuluth script was fairly widespread in 16th-century Iran. A wooden cenotaph or grave marker from the Louvre Museum in Paris [7] similarly features bands of script carved against a blank background and arranged vertically. Unlike the panel in the Aga Khan Museum Collection, however, the cenotaph contains verses from a funerary poem as well as excerpts from the Qur’an.[8]

This style of calligraphy, albeit in smaller form, can be seen on a pair of 15th-century doors from Iran in the Aga Khan Museum Collection (see AKM707).[9] The wood panels are reminiscent of similar carvings originating from the Mazandaran, an Iranian region known for its forest of khalanj wood.[10]

— Michelle al-Ferzly

Notes

[1] Makariou and Buresi, Chefs-d’oeuvre islamiques de l’Aga Khan Museum, 194–97.

[2] Lentz and Lowry, Timur and the Princely Vision, 207–8.

[3] Junod, The Path of Princes, 194–95.

[4] Graves, Architecture in Islamic Arts, 332.

[5] Kenney and Baumeister, “Damascus Room,” 333–36.

[6] Gruber, The Moon, 180–81.

[7] Louvre Museum, MAO 321, http://cartelfr.louvre.fr/cartelfr/visite?srv=car_not_frame&idNotice=33555&langue=fr.

[8] Anglade, Catalogue des boiseries de la section islamique, 152–53.

[9] These doors also include the signature of the carpenter responsible for the wood carving.

[10] Graves, Architecture in Islamic Arts, 332; Lentz and Lowry, Timur and the Princely Vision, 207.

References

Anglade, Elise. Musée du Louvre : catalogue des boiseries de la section islamique. Paris: Ministère de la Culture et de la Communication, Editions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, 1988. ISBN: 9782711821303

Gruber, Christiane, ed. The Moon: A Voyage Through Time. Toronto, ON: Aga Khan Museum, 2019. ISBN: 9781926473154

Junod, Benoît. The Path of Princes: Masterpieces from the Aga Khan Museum Collection. Geneva: Aga Khan Trust for Culture, 2008. ISBN: 9789728848484

---, Margaret S Graves, et al. Architecture in Islamic Arts: Treasures of the Aga Khan Museum. Geneva: Aga Khan Trust for Culture, 2011. ISBN: 9780987846303

Kenney, Ellen, and Mechthild Baumeister, “Damascus Room.” In Masterpieces of from the Department of Islamic Art. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art; New Haven, Connecticut: Distributed by Yale University Press, 2011, 333–6. ISBN: 9781588394347

Lentz, Thomas W., and Glenn D. Lowry. Timur and the Princely Vision: Persian Art and Culture in the Fifteenth Century. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1989. ISBN: 9780874747065

Makariou, Sophie and Monique Buresi. Chefs-d’oeuvre islamiques de l’Aga Khan Museum (accompagne l’exposition organisée à Paris, Musée du Louvre, du 5 octobre 2007 au 7 janvier 2008). Milan: 5 Continents; Paris: Musée du Louvre, 2007. ISBN: 9788874394425

Note: This online resource is reviewed and updated on an ongoing basis. We are committed to improving this information and will revise and update knowledge about this object as it becomes available.